Blogs

Romantic Novelists' Association Annual Awards

Fri, 01/03/2013 - 16:44 — Mary

In Regency times, the success of a social occasion was judged on how great a crush it was. Using that yardstick, the Romantic Novelists’ Association awards event on Tuesday was a triumph. Nearly two hundred and fifty novelists, agents and publishers, together with members of the press, stood shoulder to shoulder, drinking champagne and nibbling canapes, all to hear who had won in each of the categories for Romantic Novel of the year (the RoNAs). There were well-established best-selling novelists, those less well-known and others yet to be published, all mingling and enjoying the occasion. Writing is a solitary occupation, so when writers get together they have plenty to talk about and the decibels were sky high.

In Regency times, the success of a social occasion was judged on how great a crush it was. Using that yardstick, the Romantic Novelists’ Association awards event on Tuesday was a triumph. Nearly two hundred and fifty novelists, agents and publishers, together with members of the press, stood shoulder to shoulder, drinking champagne and nibbling canapes, all to hear who had won in each of the categories for Romantic Novel of the year (the RoNAs). There were well-established best-selling novelists, those less well-known and others yet to be published, all mingling and enjoying the occasion. Writing is a solitary occupation, so when writers get together they have plenty to talk about and the decibels were sky high.

Eventually silence was attained and the business of the evening went forward with a short speech by our Chairman, Anne Ashurst and then the announcement of the winners, whose trophies were presented by Richard Madeley and Judy Finnigan.

First up was the RoNa Rose, a separate award specifically for shorter novels and serials which concentrate on the developing relationship between the hero and heroine. This was won for the second year running by Sarah Mallory, with Beneath the Major’s Scars published by Harlequin Mills & Boon Historical.

The winners in each category of the main award were:

The Contemporary Romantic Novel was won for the second year running by Katie Fforde with Recipe for Love published by Arrow.

The Epic Romantic Novel was won by Rowan Coleman with Dearest Rose published by Arrow.

The Historical Romantic Novel was won by Charlotte Betts with The Apothecary’s Daughter published by Piatkus.

The Romantic Comedy category was won by Jenny Colgan with Welcome to Rosie Hopkins’ Sweetshop of Dreams published by Sphere

And the winner of Young Adult Romantic Novel was Witchstruck by Victoria Lamb published by Corgi.

These winners will go forward to the final judging for the Romantic Novel of the Year to be announced in May.

A lifetime achievement award was also presented to Sophie Kinsella whose acceptance speech was warmly applauded.

Congratulations to all the winners and commiserations to those who reached the short lists. It must have been a difficult decision for the judges because there were so many good books in the short lists. I came away clutching a handful which I shall enjoy reading.

To learn more about the RNA and see more pictures go to: www.romanticnovelistsassociation.org

The Authors of the Historical Romantic Novelist short list: Pamela Hartshorne, Christina Courtney, Charlotte Betts, Kate Furnivall, Mary Nichols, Susanna Kearsley

The Authors of the Historical Romantic Novelist short list: Pamela Hartshorne, Christina Courtney, Charlotte Betts, Kate Furnivall, Mary Nichols, Susanna Kearsley

Shortlisted

Thu, 24/01/2013 - 17:17 — Mary I am thrilled to have my novel, THE KIRILOV STAR, published by Allison and Busby, shortlisted for the Historical category of the Romantic Novelists Association’s annual RoNA (Romantic Novel of the Year) Award. The winners of each of category will be announced at a special event in London on 26th February by Judy Finnigan and Richard Madeley.

I am thrilled to have my novel, THE KIRILOV STAR, published by Allison and Busby, shortlisted for the Historical category of the Romantic Novelists Association’s annual RoNA (Romantic Novel of the Year) Award. The winners of each of category will be announced at a special event in London on 26th February by Judy Finnigan and Richard Madeley.

I have been fascinated by Russian history ever since I read the Russian classics at school (in English I hasten to add), especially the assassination of Tsar Nicholas and his family and the widespread belief that Grand Duchess Anastasia had survived, which has since been disproved. The Kirilov Star is a book I have wanted to write for a long time, but hesitated doing. Its synopsis lay in a drawer for years while I concentrated on other things. But then I decided if I didn't go ahead and write it, I never would. I am glad I did.

Besides, Historical Romance, the other RoNA categories are: Contemporary Romance; Epic Romance; Romantic Comedy and Young Adult. The winner of each category will go forward for the overall Romantic Novel of the Year award which will be announced in May.

There is also a separate award called the RoNA Rose for shorter fiction, known as category/series romance. This award will also be announced on 26th February. I have twice been shortlisted for this.

The Romantic Novelists’ Association was founded in 1960 to support and encourage writers of romantic fiction and to promote the genre. It has been steadily gaining prestige among writers, agents, publishers and other publishing professionals and the awards are highly prized. It also actively promotes new writers with its New Writers Scheme and many have been published as a result of joining that. I have been a member since its very early days.

You can see all the short listed books on the RNA’s website: www.rna-uk.org

Do you need to be a historian to write historical novels

Sun, 20/01/2013 - 10:19 — MaryDo you need to be an historian to write historical novels?

Out of the blue last year I was asked to take part in a series of blogs about writing historical novels which Steve Rossiter of the Australian Literature Review was putting together to begin in January this year. He has gathered together some very good historical novelists to take part, each contributing one blog a month. He wanted all twelve in by November. I was at first daunted by the thought of doing them, but I enjoy a challenge and as I was, at the time, between novels, I agreed and duly sent off my twelve blogs together with some pictures. My first effort has gone on line at http://writinghistoricalnovels.com where you can read my piece and those of the other historical novelists.

This is what I wrote.

I write historical novels, but I make no claim to be an historian in the academic sense. I am sure I am not unique in saying I hated history at school. All those dates and wars and politics left me cold. It was the only subject of the those I took for School Certificate that I failed. Why then, did I end up writing historical novels?

I write historical novels, but I make no claim to be an historian in the academic sense. I am sure I am not unique in saying I hated history at school. All those dates and wars and politics left me cold. It was the only subject of the those I took for School Certificate that I failed. Why then, did I end up writing historical novels?

Two people had a lasting influence on me. The first was my father. He was Dutch, so English was his second language, but he was meticulous in its use and would brook no sloppiness in his children. He maintained reading was the best way to learn and subscribed to a book club which produced classics like: Lorna Doone, Wuthering Heights, Jane Eyre, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Tom Jones, Gulliver’s Travels, The Woman in White, Barchester Towers etc. etc. plus the complete works of Shakespeare, and I was encouraged to read them at a very early age, long before I could understand what they were all about. It was no hardship. I was an avid reader and read everything I could lay my hands on whether it was suitable reading for a child or not. I think these books coloured my writing style. I was told by one editor, that my ‘voice’ didn’t work well with a contemporary novel and I ought to stick to historical.

The second great influence was my grandmother. I was sent to stay with her during the Second World War and spent some of my most formative years in the country, living on a small holding with no electricity, gas, main drains, sewerage or telephone, just four walls, a roof and a few acres of land. The loo was down the garden, the bath hung on a hook on the back place wall and the cooking was done on the kitchen range. When it got dark we sat by the light of an oil lamp and lit our way to bed with a candle.

Grandma was an indomitable lady who was midwife, nurse and confidante to the whole village of Necton in Norfolk from before the first World War until the coming of the National Health Service in 1948. She was not unique in what she did, there were thousands of women doing the same job. They were referred to as 'the handywoman' or 'the woman you sent for.' And when she was sent for, she always went, whatever the time of day or night.

She was a fund of stories and when she began with, ‘That time o’ day…’, she wasn't talking about hours and minutes but times gone by and I knew there was a story coming. She was the soul of discretion so I never heard much about her work, which was probably not fit for childish ears in any case, but about her early life and times. She told me she had run away from home when she was eight. Her mother had died in childbirth and as the eldest of four girls, she was expected to help in the running of the home. 'I didn't reckon a lot to that,' she told me. She walked the four miles from her home in Swaffham to Necton where her grandparents had a brickmaking business. They told her she could stay on condition she helped make the bricks. She never went to school again.

I heard about making bricks, my grandfather's work as a shepherd, their disastrous wedding day told with the humour that never left her, my mother's illness as an infant, helping the doctor take out a child's tonsils on the window sill of a cottage during an earthquake, about the first World War and the Zeppelins. I soaked them all up. What she was telling me was social history, made more interesting because it was told by someone I knew and loved. Later, I wrote her biography, THE MOTHER OF NECTON.

It was only a short step from listening to stories of times past to reading about them and then to writing my own, though success in writing took some years, a lot of hard work and dogged persistence. Whether the history came first or the need to write, I can’t tell, but both have served me well over the years.

So the answer to my own question is, no, you don’t need to be an historian to write historical novels.

.

Writing the Mini-series

Wed, 19/12/2012 - 15:37 — MaryWhen I wrote The Captain’s Mysterious Lady, it was a one-off, a change from writing Regency books. The Georgian era intrigued me for its lawlessness and the way crime was dealt with at the time.

There was no regular police force. The streets were patrolled by the watch appointed by the parish and they often consisted of old men, no match for hardened criminals. Above them were unpaid constables, who were obliged to do their spell of duty whether they wanted to or not. They could arrest people caught in the act or brought to them by a complainant, but detective work was unheard of. The only real deterrent to crime was the harshness of the penalty once the perpetrator reached court. But that was often counter-productive; one might as well be hanged for a sheep as a lamb.

There was no regular police force. The streets were patrolled by the watch appointed by the parish and they often consisted of old men, no match for hardened criminals. Above them were unpaid constables, who were obliged to do their spell of duty whether they wanted to or not. They could arrest people caught in the act or brought to them by a complainant, but detective work was unheard of. The only real deterrent to crime was the harshness of the penalty once the perpetrator reached court. But that was often counter-productive; one might as well be hanged for a sheep as a lamb.

My hero, Captain James Drymore, searching for the murderers of his wife and intent on vengeance, is, for the first time since it happened, side-tracked into helping Amy Macdonald, a young lady he meets on a coach who is obviously in distress. She has witnessed a crime which has so traumatised her she cannot remember the details, though it gives her nightmares. In solving her mystery, James finds himself torn between his determination for revenge and his growing feelings for her. By the time his dilemma is solved, he has decided something must be done about solving crime. He consults Sir Henry Fielding who is trying to interest Parliament in the idea for what became known as the Bow Street Runners, but their scope was limited and did not include detection work. And they did not operate outside London unless, of course, they were on the track of a known criminal. James sets up a group of like-minded gentleman, all rich enough not to require payment for their services. Not for them the taking of bribes as other thieftakers were known to do. They do it for the love of adventure and to make the country a safer place to live.

My editor at Mills & Boon liked this book so much she suggested it could be the start of a mini-series about Georgian crime and asked me to think of a name for the group. I invented The Society for the Discovery and the Apprehension of Criminals which became known as The Piccadilly Gentlemen’s Club. I wrote four books initially: The Captain’s Mysterious Lady (shortlisted for the RNA’s Love Story of the Year award); The Viscount’s Unconventional Bride; Lord Portman’s Troublesome Wife and Sir Ashley’s Mettlesome Match. Each deals with a different member of the group and a different crime, in the solving of which each finds the love of his life. Needless to say the heroines all appear to be in league with the criminals, until events prove otherwise.

The books have proved very popular and after a break to write another Regency, I’ve written two more. The Captain’s Kidnapped Beauty. (Different captain; this time a sea-farer). Charlotte Gilpin, the daughter of a wealthy coachmaker has been kidnapped, but this is no simple kidnapping; the victim is taken on board a ship bound for Portugal and Alex must needs follow. His efforts to bring her safely back to England are thwarted by the lady herself who has her own ideas about whom to trust.

All of these involved a certain amount of research. Quite apart from the usual period research like costume, manners, food and transport, I needed to know about the crime my hero was investigating. Murder and theft were fairly easy, but others were more interesting. For instance, Lord Portman was investigating coining. I found this subject fascinating. Forgers made new coins by covering base metal in a thin film of gold and using stolen or forged stamps to imprint the head and tail. Or they would file down the edges of gold coins and use the filings to make more coins. Then they needed a small army of people to pass them into circulation which they did by offering a sovereign to buy an item costing only a few pence. The crime became so widespread it was threatening to destabilise the currency of the country.

All of these involved a certain amount of research. Quite apart from the usual period research like costume, manners, food and transport, I needed to know about the crime my hero was investigating. Murder and theft were fairly easy, but others were more interesting. For instance, Lord Portman was investigating coining. I found this subject fascinating. Forgers made new coins by covering base metal in a thin film of gold and using stolen or forged stamps to imprint the head and tail. Or they would file down the edges of gold coins and use the filings to make more coins. Then they needed a small army of people to pass them into circulation which they did by offering a sovereign to buy an item costing only a few pence. The crime became so widespread it was threatening to destabilise the currency of the country.

Sir Ashley is investigating smuggling. This was big business in the south west and on the Norfolk coast, which was my particular concern. Smugglers were not the romantic vagabonds of popular myth. They were ruthless outlaws and thought nothing of ending the life of anyone who tried to thwart them. There were some truly big battles between smugglers and the excise men trying to arrest them. The communities in which they worked were either hand in glove or turned a blind eye. They dare not do otherwise.

In the Captain’s Kidnapped Beauty (short listed for the Rona Rose award, previously the Love Story of the Year) my research centred on coach-making as a business. Everyone who travelled any distance had to go by coach, whether it was a stage coach or one they owned or hired and good coachmakers (especially those in London) were the multi-millionaires of Georgian times. The aristocrats and wealthy citizens usually owned more than one coach, depending on the use to which they wanted to put it, much as the wealthy (and not so wealthy) today own more than one motor car. Long distance travel, especially on poor roads, needed a sturdy and comfortable vehicle. Coaches used in town could be lighter and more showy. And of course there were sporting vehicles for young bloods and sedate gigs for the more down to earth. And there were hundreds of hackney cabs for hire in the Capital. According to the Times Newspaper, the number of two and four wheeled carriages in England in 1787 was put at 16,000. My coachmaker is wealthy enough for someone to think of kidnapping his daughter.

I thought that might be the end of the series, but then I added one more, just to round the series off. The Commodore’s Inconvenient Wife, will be published next year. I’ve brought the action forward a generation and the hero is the son of the founder of society and most of the action for this takes place in France at the time of the Revolution. That time is a storehouse of ideas for the historical writer. You have only to think of Baroness Orczy and The Scarlet Pimpernel books and Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities, one of my favourite Dickens books, if only for the first sentence and the last.

I’ve done linked books before, but this mini series has been by far the longest. One of the reasons for doing them is that a minor character becomes interesting enough to call for a book of their own. In this case it was a group of men and a string of crimes.

I have really enjoyed doing them.

If you want to know more about them take a look at my website: www.marynichols.co.uk

Wartime rationing

Sun, 11/11/2012 - 15:01 — MaryI remember World War 2 very vividly although I was only a child at the time and writing about it in The Girl on the Beach, meant doing some research, particularly about food rationing and that set my memory off. The conversations in the queues were often about the progress of the war, the blitz and the damage caused, the casualties, whose son had been posted missing or who had been found safe as a prisoner of war, and the miseries of travel, but more often than not it was about food and how to make the rations go round.

Much of Britain’s food before the war was imported, but what with the ships being needed for conveying troops and armaments and the menace of u-boats, this had to be severely curtailed. We had to rely more on food produced at home. Farmers were dogged by regulations about what they grew and how they grew it, and everyone was encouraged to grow vegetables. ‘Dig for Victory’ was the slogan. Flower beds were dug up, even in municipal parks, in order to grow vegetables. And pig clubs sprang up everywhere and swill buckets were left in schools and restaurants to feed them.

Much of Britain’s food before the war was imported, but what with the ships being needed for conveying troops and armaments and the menace of u-boats, this had to be severely curtailed. We had to rely more on food produced at home. Farmers were dogged by regulations about what they grew and how they grew it, and everyone was encouraged to grow vegetables. ‘Dig for Victory’ was the slogan. Flower beds were dug up, even in municipal parks, in order to grow vegetables. And pig clubs sprang up everywhere and swill buckets were left in schools and restaurants to feed them.

The war was less than a month old when ration books were issued to everyone, each with the name of its owner on the front and the books had to be registered with a grocer, whose stocks were governed by the number of people registered with him. . Rationing began in January 1940, with sugar at 12ozs per week, butter 4ozs and bacon and ham 4ozs. (16ozs to the pound, a pound is not quite 500 grams, so 4ozs is roughly 125 grams) Two months later meat was rationed by price at one shilling and tenpence worth a week. (A shilling converted to 5p in 1972 but that is meaningless now) Because it was rationed by price, the cheaper cuts gave you more for your money and there were many recipes published and broadcast on the BBC to make the best use of them. Meat was followed by cheese and then preserves, margarine (2ozs a week) and cooking fat (also 2ozs). Eggs and milk were allocated rather than rationed and their supply varied. Bread was never rationed during the war, (although it was afterwards) but we ate the National Loaf which was a grey colour and was supposed to be more nutritious. As the war progressed the amounts were changed according to available supplies. Food that was not rationed was often in short supply and long queues formed the minute word went round that stocks had arrived in the shops and once the supplies of tinned fruit and vegetables were used up there were no more. Onions, most of which had previously been imported from the Channel Islands, were like gold dust and exchanged hands for exorbitant sums. Oranges, lemons and bananas were unheard of.

I remember the mother of one of my friends gave us some bread and butter (‘Scrape it on and scrape it off again.’ my mother used to say) on which she had spread something she called mock banana. It was mashed potato flavoured with banana essence and it was pretty awful. Children of five who were given bananas at the end of the war didn’t know what to do with them and often tried to eat them skin and all!

I was staying in the country with my aunt who had befriended some American airmen from the nearby base. They told her they had loads of oranges, many of them over-ripe. My aunt suggested they would make good wine if only they had the sugar. To her surprise two sacks of oranges and a sack of sugar was delivered by jeep for her to make the wine. She didn’t have a vessel large enough and so used the copper which stood in the corner of the kitchen. For weeks we had to endure the smell as it fermented. The resulting wine was bottled and the Americans came and picked them up, leaving a few for my aunt’s own use. We were going to my grandmother’s for Christmas and took a couple of bottles on the train with us, putting them with our luggage on the rack above our heads. A little while into the journey there was a loud explosion and everyone dived for cover, thinking they were being bombed. It was only when the sticky orange mess dripped down from the rack did we realise the wine had blown its cork and fear changed to merriment. It took ages to clean ourselves up when we arrived at our destination.

On another occasion while staying with my grandmother in the country, her cat brought in a rabbit she had caught. Grandma shut all the doors and endeavoured to relieve the cat of her catch. Puss was understandably loath to let it go and there resulted a chase round furniture, under the table, round chairs, behind cupboards worthy of a comedy film. The poor cat, hampered by her burden which was almost as big as she was, eventually had to drop it and we had rabbit stew for dinner. I think the cat had her share.

Rabbits were also caught at harvest time. Everyone stood round shoulder to shoulder with clubs in their hands as the reaper felled the last few rows of standing corn and the rabbits ran out. I was too squeamish and let a rabbit run out between my legs, much to my grandfather’s fury. My brother bagged one, but it was taken off him by one of the grown-ups. Again we had rabbit for dinner. We had pigeon pie in those days too, anything to stretch the meat ration. My mother, like many another housewife, became adept at making a few ounces of mince go round the family with lots of vegetables and good gravy.

I remember my mother and her sister going to a dance at the American base and coming back with a huge joint of beef. My grandfather was furious and called them Jezebels, a favourite word of his. He would have made them take it back, but Grandma was more of a realist and we had a feast the following day. On one occasion when Mother was putting me to bed, I complained of being hungry. Her answer was ‘Go to sleep and forget about it.’ We were never really hungry, never starving as other people in the world were, and my complaint was really only that I felt a bit peckish.

It seems unbelievable now, when we think nothing of spreading what would have been half a week’s butter ration on a single slice of toast, or cracking two eggs into a pan for our breakfast, when in those far-off days we were lucky if we had one a week. Everything was bulked out with vegetables and we ate more than the five-a-day we are exhorted to eat nowadays. But according to the statistics we, as a nation, were far healthier. Obesity was not a problem. But I don’t think I’d want to go back to those times for all that.

Details of The Girl on the Beach and all my other books can be found on: www.marynichols.co.uk

Finding Inspiration

Sun, 04/11/2012 - 15:44 — MaryI am often asked how I get the ideas for my books. The answer is anywhere and everywhere: from books, newspapers, things I've experienced, stories people tell me.

For instance, just after WW2, my mother worked in a home for unmarried mothers. The girls (some of them very young) were taken there a few weeks before the birth to have their babies who were then taken away for adoption. A week or two later they were sent home and expected to get on with their lives as if nothing had happened. That story stuck in my mind. I couldn’t help wondering how the poor mothers must have felt. Could that be a basis for a story? What if my heroine was married to a serviceman who was away fighting in France in the Great War? What if she fell in love with someone else? What if he, too, was sent away to France, leaving her pregnant? That would have been the ultimate disgrace in those times. What if her parents insisted on having the child adopted? How would she feel? How would she cope? I asked myself what kind of life would this baby have? What would her adoptive parents be like? Rich or poor? Would she be cared for and loved? Would she be told the story of her birth or would it be kept a secret from her? What if the real mother does find her daughter again, how would she feel? What could she do about it? In answering those questions I had The Summer House.

On the other hand, The Fountain was inspired by a competition run by my local newspaper some time before to design a new fountain to go on the market square. It resulted in hundreds of entries, some well drawn, others scribbled on the backs of envelopes. None of them was ever used, except by me as inspiration. I set it between the wars when it was easier for unscrupulous public servants to get away with corruption. If my heroine was married to such a one, how would she react? Would she support him or would she rebel?

The Kirilov Star was the result of my fascination with the Russian Revolution and the fate of the aristocracy, particularly the story of the possible survival of Grand Duchess Anastasia, (since disproved), but supposing my heroine did survive, the only one in her family to do so, and was brought out of Russia as a child to be adopted and brought up in England? How strong would her Russian roots be? Would the pull be strong enough to make her abandon a comfortable life to go in search of them?

The Kirilov Star was the result of my fascination with the Russian Revolution and the fate of the aristocracy, particularly the story of the possible survival of Grand Duchess Anastasia, (since disproved), but supposing my heroine did survive, the only one in her family to do so, and was brought out of Russia as a child to be adopted and brought up in England? How strong would her Russian roots be? Would the pull be strong enough to make her abandon a comfortable life to go in search of them?

The Stubble Field also came about from two books I had been reading: The Workhouse by Norman Longmate and The Railway Navvies by Terry Coleman. I asked myself what it must be have been like to be forced into the workhouse where husbands were separated from wives, brothers from sisters and what happened to the children when they went out into the world? Did they ever see their siblings again? The hard lives of the navvies fascinated me: all those miles and miles of railway lines built with nothing but shovels and strong muscles. Together they gave me my story. The book is long out of print, but now renamed A Line Through Chevington, it is once again on sale as an e-book, together with its sequel Promises and Pie Crusts.

Publishing ebooks

Wed, 24/10/2012 - 08:29 — Mary When I began writing novels many moons ago, it was done by hand and then laboriously copied onto a typewriter with a carbon copy. If I made a mistake it was out with the tippex or rip the page out and start again. With my first royalties I bought a golf ball typewriter, huge and heavy, but it dealt with mistakes more easily. The next step was an Amstrad word processor, then a PC and learning to use Word, but even so, manuscripts had to be printed out and posted. Then came the internet and email and life became a whole lot easier. I now submit my books and correct proofs by email.

When I began writing novels many moons ago, it was done by hand and then laboriously copied onto a typewriter with a carbon copy. If I made a mistake it was out with the tippex or rip the page out and start again. With my first royalties I bought a golf ball typewriter, huge and heavy, but it dealt with mistakes more easily. The next step was an Amstrad word processor, then a PC and learning to use Word, but even so, manuscripts had to be printed out and posted. Then came the internet and email and life became a whole lot easier. I now submit my books and correct proofs by email.

And now we have ebooks.

After over fifty novels published in the traditional way, I decided the time had come to tackle ebook publishing. It has been a steep learning curve, but with considerable help from my daughter-in-law and loads of advice from my friends in the Romantic Novelists Association who have taken the plunge before me, I now have several ebooks to go alongside those of my print publishers.

The Stubble Field was the first family saga I had published way back in 1991, so I started with that. Orphaned brother and sister, Sarah Jane and Billie Winterday are forced to go to the dreaded workhouse when their parents die. They are separated and from then on their lives follow different courses, although every now and again, they are within a whisker of being reunited. I wrote the original story from both points of view but it became impossibly long and I knew that would not be acceptable, so I split it in two. Sarah Jane’s story was published as The Stubble Field, but when I sent the sequel to the publisher, I had one of those setbacks familiar to every writer. Billie’s story was turned down on the grounds that historical novels were out of fashion and no one was buying them. I was stuck. No publisher would take a sequel to a book published elsewhere.

So many people who read and enjoyed the first book have asked me ‘What happened to Billie?’ the opportunity to e-publish was heaven-sent. The Stubble Field has become A LINE THROUGH CHEVINGTON (my original title) and Billie’s story is now available as an ebook with the title: PROMISES AND PIE CRUSTS, so now they can be bought and read together. These were followed by THE POACHER’S DAUGHTER and that one alone has made the effort worthwhile.

Some of my early Mills & Boon books were out of print and I regained the rights to these and we converted these into ebooks too, updating and finding them new covers. There will probably be more as titles become available.

How long or how successful the ebook phenomenon will be there is no telling. It had its plus and minus side, but at the moment it is giving my out-of-print books a second airing.

Being a guest on a blog

Sun, 30/09/2012 - 09:48 — MaryIt is always gratifying to be asked to be a guest on someone else's blog, especially someone like the prolific Kate Hardy/Pam Brooks. Kate has been celebrating her 50th book for Mills & Boon ( The Hidden Heart of Rico Rossi)with a blog party and invited me to be a guest. You'll find it on her blog. http://katehardy.blogspot.co.uk/2012/09/50th-party-blog-guest-mary-nichols.html

There are others at the party,of course, writers like Michelle Styles, Nell Dixon, Liz Fielding Kate Walker, Nicola Cornick, Sharon Kendrick, Carol Townend and Jan Jones, among them. I was flattered to be included.

This was a Mills & Boon party, but Kate, as Pam Brooks, writes non-fiction books too, such as Researching the History of your House, which is fascinating and full of interesting facts and good advice.

And just to blow my own trumpet, Julie Bonello has given me a fantastic review of The Kirilov Star which she posted on her singles titles website, her own blog, Smashwords and Amazon. Wonderful and I'm really thrilled. You will find the link on the book's page in All my Books>Mainstream/Sagas in the menu on the left.

Doing the promotion

Tue, 28/08/2012 - 13:43 — Mary  The research is done, the book written, the publisher is pleased with it, the cover is chosen, the blurb written and the printer has done his work. Publication day has arrived. Time to celebrate, yes? Well, no. There is still work to be done.

The research is done, the book written, the publisher is pleased with it, the cover is chosen, the blurb written and the printer has done his work. Publication day has arrived. Time to celebrate, yes? Well, no. There is still work to be done.

You need to let your readers know it is out there for them to buy and that’s where promotion comes in. As a child I was taught not to boast, no one liked a show-off. If you have done something praiseworthy, then let that something speak for itself. I remember my father telling me that in ancient Rome (or was it Greece?) it was a punishable offence to boast.

Consequently putting myself forward comes hard to me, as I suspect it does for many writers.But as things are today with literally millions of books out there to choose from, why should anyone pick up mine, especially if I do nothing to point out that it is available?

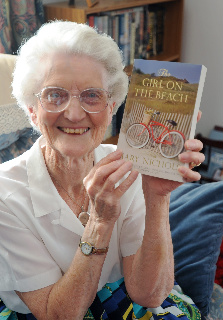

Photo by kind permission of The Cambridge News

So, you persuade the local book shop to let you do a signing. This is my least favourite way of doing things. No one may come in the shop while you are there, or there may be a stream of people coming and going who look away when they see you sitting there beside your pile of books with a pen in your hand. Some might pick up one of the books, leaf through it and put it down again. You have to pluck up your courage to speak and sometimes that results in a sale. Sometimes you have an interesting conversation and still no sale. But will they remember you afterwards?

The next thing is to contact the local newspaper and ask for a review of the book and/or an interview. If they have already done a piece about you for previous books, then you need to tell them why this is different, a hook on which to base the article. You are at the mercy of the reporter here; sometimes they do a good job and sometimes manage to get things wrong. You wish they would concentrate on the book and not on how old you are, but it is publicity for your book, all grist to the mill.

You fill in the form to have yourself put on the local Women’s Institute list of speakers and that can lead to other groups getting in touch with you. ‘So and so enjoyed your talk and will you come and speak to our group?’ Sometimes you need to search them out yourself.

A launch is different, you give a short talk, usually after the shop has shut in the evening, and invite questions. A joke or two against yourself often helps; laughter is a great way of engaging with an audience. And it is very gratifying to have a full house.

And then there’s the electronic side of things. There’s a world out there, a huge ocean, not just your own little pond, and a stone thrown into it causes ripples that spread far and wide. I have a website which I keep up to date and post blogs, not only on my own site, which is new, but as a guest on others, but I still cannot bring myself to tweet, especially as blatant promotion is frowned on and may have a negative effect. I haven’t the time to engage in meaningless chatter. I have another book to write. And that’s what I like best.

Weather in times past

Thu, 02/08/2012 - 16:54 — MaryI drove home in a cloudburst the other day. The windscreen washers had a job to clear the screen and I could hardly see where I was going. It set me thinking about our English weather and the dreadful so called summer we have had, with the odd very warm day interspersed with days of heavy rain. Is our weather any worse than it used to be in years gone by?

As a writer of historical fiction, I could invent the weather to fit my plot but I like to stick to the facts, if I can, so whenever I come across the mention of weather in an historical record, I like to make a note of it and it seems to me, our climate has always been unpredictable. There have always been heavy snowfalls, gales, flooding and heat waves and ever since 1659, there have been weather records.

I have recently been writing about the 18th Century when the nine years from 1751 - 1760 were the wettest for nearly a hundred years and in March 1774, there was deep snow and frost and then a rapid thaw which led to extensive flooding. A gale and storm surge in 1740 inundated the Suffolk coast and carried away the last of the church at Dunwich, a town already being eroded by the sea and now completely gone. It is said you can still hear the church bells ringing when the sea is rough. In June and July 1783, a series of volcanic eruptions in Iceland sent clouds of sulphuric dust into the atmosphere resulting in a blue haze all over Europe and thousands of deaths. In 1794 a snowstorm swept across Scotland and left behind it over 1800 dead sheep, nine cattle, three horses, 45 dogs, two men and one woman beside innumerable smaller animals, all heaped together. There was snow in London in June 1791 but it soon disappeared.

In Regency times, the winter of 1813/14 was one of the coldest on record with huge snowfalls, and on the 27th December, the fog was so dense visibility was down to five yards in places and the Prince Regent on his way to St Albans to visit the Earl of Salisbury was obliged to turn back. The Frost Fair on the Thames in February 1814 was the last time the Thames froze bank to bank, although ice floes were recorded in the winter of 1894/95.

1816 was called the year without a summer, not only in England but all over the world, caused by a huge volcanic explosion in Mount Tamboura in the Dutch East Indies, which sent a dust column thousands of feet into the air. The debris, including vast quantities, of sulphur took a year to circulate, its sheer volume obliterating the sun. Without the sun temperatures dropped dramatically and there was constant rain. In the UK, crops rotted in the fields and even those that were harvested rotted in the barns. Farm labourers were put out of work and added to the unemployed soldiers returning from the war with Napoleon.

On the 28th December 1879, the Tay Bridge in Scotland was blown over in a gale while a train was crossing it and 75 lives were lost. In the winter of 1890/91 the ice was so thick, the rivers Severn and Avon could be crossed on it by ordinary road traffic.

Coming to more recent times, the wet summers of the Great War are legendary when the troops wallowed in mud; and the winter of 1939/40, the first of the Second World War, had a lot of snow followed by a glorious summer when the Battle of Britain raged over the skies of southern England. There was a heat wave in September of that year with temperatures in the 90s F.

1946/47 was one of the harshest on record causing fuel and food shortages from January to March. When the thaw came it brought rain with it which, added to the melting snow, caused widespread floods when thousands of properties were damaged. A severe gale on the night of 16th/17th April together with high river levels breached the dykes in the fens and thousands of acres of arable land were flooded. Almost the same thing happened on the night of 31st January 1953. Gales with speeds of up to 100 mph, coupled with exceptionally high tides caused major flooding on both sides of the North Sea. It was a terrifying night along the east coast of England, homes were washed away and 300 lives were lost.

1962/63 was another severe winter when it was possible to skate from Cambridge to Ely on the river and the ice was so thick on the ponds I remember a jeep being driven across a lake towing an upside-down wooden table in which several children enjoyed a ride. That December too, we had the last great smog in London caused by coal smoke and sulphur dioxide products over ten times their normal concentration and, as a result thousands died of lung problems. Since then we have had smoke free zones.

These records are grist to the mill for a writer of historical novels, but I am left wondering, is the weather any worse than it used to be? Fortunately nowadays we have weather warnings and flood defences and highly sophisticated farm machinery to mitigate the damage, though building on flood plains and covering our gardens with tarmac and concrete is not helping. All the same I think we are lucky compared with what our forebears had to put up with.