Finding Inspiration

I am often asked how I get the ideas for my books. The answer is anywhere and everywhere: from books, newspapers, things I've experienced, stories people tell me.

For instance, just after WW2, my mother worked in a home for unmarried mothers. The girls (some of them very young) were taken there a few weeks before the birth to have their babies who were then taken away for adoption. A week or two later they were sent home and expected to get on with their lives as if nothing had happened. That story stuck in my mind. I couldn’t help wondering how the poor mothers must have felt. Could that be a basis for a story? What if my heroine was married to a serviceman who was away fighting in France in the Great War? What if she fell in love with someone else? What if he, too, was sent away to France, leaving her pregnant? That would have been the ultimate disgrace in those times. What if her parents insisted on having the child adopted? How would she feel? How would she cope? I asked myself what kind of life would this baby have? What would her adoptive parents be like? Rich or poor? Would she be cared for and loved? Would she be told the story of her birth or would it be kept a secret from her? What if the real mother does find her daughter again, how would she feel? What could she do about it? In answering those questions I had The Summer House.

On the other hand, The Fountain was inspired by a competition run by my local newspaper some time before to design a new fountain to go on the market square. It resulted in hundreds of entries, some well drawn, others scribbled on the backs of envelopes. None of them was ever used, except by me as inspiration. I set it between the wars when it was easier for unscrupulous public servants to get away with corruption. If my heroine was married to such a one, how would she react? Would she support him or would she rebel?

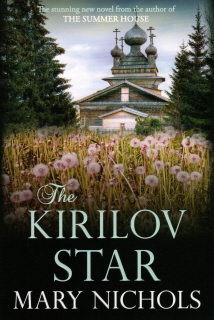

The Kirilov Star was the result of my fascination with the Russian Revolution and the fate of the aristocracy, particularly the story of the possible survival of Grand Duchess Anastasia, (since disproved), but supposing my heroine did survive, the only one in her family to do so, and was brought out of Russia as a child to be adopted and brought up in England? How strong would her Russian roots be? Would the pull be strong enough to make her abandon a comfortable life to go in search of them?

The Kirilov Star was the result of my fascination with the Russian Revolution and the fate of the aristocracy, particularly the story of the possible survival of Grand Duchess Anastasia, (since disproved), but supposing my heroine did survive, the only one in her family to do so, and was brought out of Russia as a child to be adopted and brought up in England? How strong would her Russian roots be? Would the pull be strong enough to make her abandon a comfortable life to go in search of them?

The Stubble Field also came about from two books I had been reading: The Workhouse by Norman Longmate and The Railway Navvies by Terry Coleman. I asked myself what it must be have been like to be forced into the workhouse where husbands were separated from wives, brothers from sisters and what happened to the children when they went out into the world? Did they ever see their siblings again? The hard lives of the navvies fascinated me: all those miles and miles of railway lines built with nothing but shovels and strong muscles. Together they gave me my story. The book is long out of print, but now renamed A Line Through Chevington, it is once again on sale as an e-book, together with its sequel Promises and Pie Crusts.