Mary's blog

Criminal Conversation

Mon, 28/09/2015 - 08:51 — Mary Anyone would think criminal conversation means plotting to commit a crime or perhaps talking about it afterwards. Not so. It was an action brought by a husband for compensation for the infidelity of his wife and was common in the late 18th and early 19th centuries with large sums of money involved. Only the wealthy could afford to take such action and it did not necessarily involve divorce.

At that time the only grounds for divorce which allowed remarriage was adultery and the law was different for men and women. A man could divorce his wife for a single act of infidelity, a woman could only sue for divorce if the adultery was accompanied by life-threatening cruelty. This at a time when a man was allowed to beat his wife!

Louisa Garret Anderson, daughter of Elizabeth Garret Anderson, writing about her mother’s day in the middle of the 19th century, said: ‘To remain single was thought a disgrace and at thirty an unmarried woman was called an old maid. After their parents died, what could they do, where could they go? If they had a brother, as unwanted and permanent guests, they might live in his house. Some had to maintain themselves and then, indeed, difficulty arose. The only paid occupation open to a gentlewoman was to become a governess under despised conditions and a miserable salary. None of the professions were open to women; there were no women in Government offices; no secretarial work was done by them. Even nursing was disorganized and disreputable until Florence Nightingale recreated it as a profession by founding the Nightingale School of Nursing in 1860.’

The Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857, did little to alter this. It changed the proceedings from Parliament to a special court and allowed cruelty and desertion in addition to adultery asa valid reason for a woman to divorce a husband. Adultery alone was still not enough. Once divorced any children of the marriage became the property of the husband and the mother could be prevented from seeing her children, even when she was the innocent party.

Before 1882 and the passing of the Married Woman’s Property Act, everything a woman owned passed to her husband on marriage. He could do what he liked with it. The 1882 Act, drafted by Dr Richard Pankhurst, husband of the suffragette, Emmeline Pankhurst allowed women to retain control of their property and earnings.

Women have had to fight all the way for their rights, which brings me to the struggle to obtain the vote, which is part of the research I'm doing for my next book. It didn’t start with Emmeline Pankhurst; it had been muted many years before, and though in 1869 the Municipal Franchise Act allowed women to vote in local elections and even stand for office, nothing was done about a parliamentary vote. There were dozens of women’s suffrage societies and associations, all working towards votes for women. Accustomed to being meek and ladylike, it was not until Mrs Pankhurst and her daughters came along things hotted up. Mrs Pankhurst argued that throughout history men have fought for what they wanted with protests and riots and often with injury and loss of life. When that happened Parliament bowed to the pressure and changed the law. She organised protests and petitions and marches in which thousands took part, but the government of the day, led by Mr Asquith, would have none of it.

One MP told the women. ‘Members of Parliament are not responsible to women, they are only responsible to voters.’. Women didn’t count. The escalation in damage to property was almost inevitable. Arrest and imprisonment followed. The hunger striking came about because they were not allowed the privileges of political prisoners but were classed as criminals. Hunger strikes led to force-feeding until the women were almost at death’s door. Afraid of the backlash, the government passed what became known as the Cat and Mouse Act. The women were released to recover and when well enough were re-arrested and the whole process began again.

The suffragists were no further forward when the first world war began and they called a truce in order to work for the war effort. This they did, taking on jobs previously done by men and doing them well. As a direct result in 1918 the Representation of the People Act was passed giving the vote to women over thirty who fulfilled the minimum property qualifications. The same Act allowed all men of 21 and over to vote, so the women were still behind the men. Not until the Equal Franchise Act was passed in 1928 were women all owed to vote at 21 along with the men.

Incidentally, in 1911, many of these women avoided filling in the census forms by staying out all night on the grounds that they didn’t count. So if you are doing family history research and cannot find your female ancestor in 1911, that may be the reason.

We'll Meet Again

Thu, 20/08/2015 - 12:50 — Mary World War Two is a goldmine for a novelist. There were battles to be fought at home and abroad, secret to be kept, risky assignments, targets to reach. There were service men and women doing their bit and those left at home coping with the blitz, shortages, rationing and war work. There was great courage as well as cowardice, self sacrifice and selfishness, stoicism and impetuosity, joy and tragedy, mystery and secrecy and all of it well-chronicled.

I have written half a dozen books with a World War two background and my latest, We’ll Meet Again is no exception. I have chosen as my premise the secrets people were asked to keep in the interests of security, secrets they could not even tell their nearest and dearest.

Most people have now heard about the work being done at Bletchley Park. Towards the end of the war, around ten thousand people were working at BP and its scattered outposts. Some were in the services, some were civilians, but rank and uniform counted for very little. Each had his or her allotted task and, apart from the people they worked with, had no idea what others were doing. Mail was sent all over the country by motor cycle to be posted so that Bletchley was never identified.

With so many people of both sexes working in such a close atmosphere romance was inevitable. There is one story that a couple who married after the war did not know that each had been working at Bletchley Park until the secret came out in the seventies. Ten thousand people keeping such a vast secret is difficult to comprehend nowadays, but keep it they did. And the work that went on there is said to have shortened the war by at least two years.

My story involves two girls from very different backgrounds who work there. Lady Prudence Le Strange, daughter of an earl, is recruited, as so many were, by recommendation. Sheila Phipps has lost all her family in the first big raid of the London blitz and is living at Bletchley with her strait-laced, snobbish Aunt Constance and is taken on as a messenger. Their work is the secret they must keep.

My story involves two girls from very different backgrounds who work there. Lady Prudence Le Strange, daughter of an earl, is recruited, as so many were, by recommendation. Sheila Phipps has lost all her family in the first big raid of the London blitz and is living at Bletchley with her strait-laced, snobbish Aunt Constance and is taken on as a messenger. Their work is the secret they must keep.

But others have their own secrets and there are mysteries to solve. Pru’s father, head of the local Home Guard, is tasked with creating a secret bunker to be used to harass the enemy if there is an invasion. Her brother is sent to France to help the resistance; her fiancé is shot down over Germany and taken prisoner. Sheila thinks her brother might still be alive, but everyone tells her it’s not possible. Her boyfriend, who is in the navy, has been torpedoed and has apparently lost his life in the freezing Arctic seas. And Constance’s strange behaviour hides a secret from the past.

We’ll Meet Again is out in paperback today, 20th August, published by Allison and Busby and available from all good bookshops, price £7.99. ISBN: 9780 7490 17040

The Long March

Mon, 27/07/2015 - 11:39 — MaryBesides, the lives of German Prisoners of War in my work in progress, I needed to research British prisoners of war held in Germany. There have been many books and films about this, e.g. The Great Escape and The Wooden Horse, but I needed to find out about what has come to be known as The Long March.

In January 1945 the Russian arm was closing in on many of the British POW camps in Poland and the decision was taken by the German government to evacuate the prisoners westwards. Carrying their belongings, 30,000 prisoners were marched from the camps in groups of 200-300, in the coldest winter for many years, with heavy snow and temperatures down to minutes twenty-five degrees centigrade at times. They were ill equipped for such a march, being weak from poor rations and with inadequate clothing, they could not keep up twenty to forty kilometres a day expected of them.

At the end of each day they were found accommodation in barns, schools, factories and churches where they were supposed to be given food and a hot drink. This was usually barley soup and a hunk of bread and there was never enough of it. The guards were as hungry as the men and were hardly better clothed.

All over Germany there were columns of weary men, shuffling along country roads with little or nothing in the way of food, clothes or medical help. As they grew weaker, they abandoned belongings they could not carry. With so little food, they were reduced to scavenging, some even eating dogs, cats and rats, and digging potatoes from farmers’ fields which had been fertilised with raw sewage, resulting in dysentery. In such conditions it was inevitable that they would succumb to exhaustion and illness. Pneumonia, diphtheria and typhus were rife and frostbite from sleeping on frozen ground. The occasional Red Cross Parcel kept them from actually starving.

There was also the danger of being attacked by Allied bombers mistaking them for marching troops, and sometimes the hostility of the population who would spit or throw stones at them. Not all civilians were like that; some brought a little food and water out to them.

For those who had furthest to come the march lasted from January to April. Thousands died by the wayside. The survivors, in a pitiful condition, finally arrived in the west and were eventually freed by the Allied advance. Large numbers of them had marched over five hundred miles, and some as much as a thousand.

The first prisoners were repatriated by air. Bomber Command began what came to be known as Exodus. Over 3 days from May 4th 1945, they brought back 72,500 prisoners of war.

WW2 German Prisoners of War

Tue, 09/06/2015 - 10:43 — Mary I am currently working on a story about Karl, a German prisoner of war in World War Two who is sent to a small English farm to work, where he meets Jean, the daughter of the farmer. Fraternisation between the prisoners and the local population is forbidden, until after the war but then their problems are only just beginning.

I am currently working on a story about Karl, a German prisoner of war in World War Two who is sent to a small English farm to work, where he meets Jean, the daughter of the farmer. Fraternisation between the prisoners and the local population is forbidden, until after the war but then their problems are only just beginning.

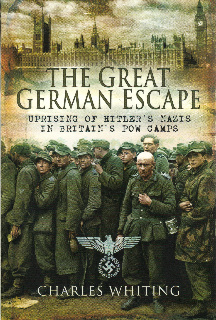

This has involved some interesting research during which I discovered that in December 1944 there was a carefully orchestrated mass break-out of German prisoners intent on marching to London and taking the city with the help of German parachutists. This was to take place simultaneously with the Ardennes counter-offensive (called the Battle of the Bulge) launched by the Germans to stem the advance of the Allies after D-Day. This is not as crazy as it seems; there were 400,000 German prisoners in captivity in the UK after D-Day (June 6 1944) and most of the British and American troops were fighting on the continen; there were few to defend London. Luckily British Intelligence, using interviews with new prisoners and information picked up at Bletchley Park, had an idea what was afoot and were able to nip it in the bud. There was no parachute drop and the German counter-attack in the Ardennes failed.

The prisoners were all interrogated when they first arrived and were categorised according to their belief in the Nazi doctrine. They were either white, grey or black. The whites were against Hitler and only wanted the war to end so that could go home; they posed no threat. The blacks were ardent Nazis and believed in the invincibility of the Fuhrer. The vast majority were grey, that is, they fought for the Fatherland and their families, and had no strong feelings about Hitler. Usually the blacks were segregated and sent to more remote camps, but with the huge influx of prisoners arriving in the autumn of 1944, some slipped through the net and were sent to ordinary camps. Put all three categories together and there was bound to be trouble. Although my book is a work of fiction, I have drawn heavily on Charles Whiting's book, The Great German Escape, for much of my research and must thank Gil Whiting for permission to use the photograph and cover on this blog.

Many of the prisoners were sent out to work on local farms. When the war ended, the UK government was slow in repatriating them because the country was desperately short of labour both on the farms and in rebuilding and repairing bomb damage, and they were n, who had come to like living in the UK, did not want to return home, especially if their home was in the Russian zone. Some went home and came back again. 24,000 settled in the UK. Another book I found useful for this aspect is Robert Quinn's Hitler's Last Army.

In December 1946 the ban on fraternisation was lifted and many prisoners were invited into British homes for Christmas. In March the following year, the ban on English girls marrying Germans was cancelled. The reaction of the population to this was mixed; some still hated the Germans and vilified the girls who went out with them. Others were more understanding and hospitable.

In December 1946 the ban on fraternisation was lifted and many prisoners were invited into British homes for Christmas. In March the following year, the ban on English girls marrying Germans was cancelled. The reaction of the population to this was mixed; some still hated the Germans and vilified the girls who went out with them. Others were more understanding and hospitable.

This is the main thread of the book but there are others which I will write about in my next blog.

Picture by kind permission of The History Press.

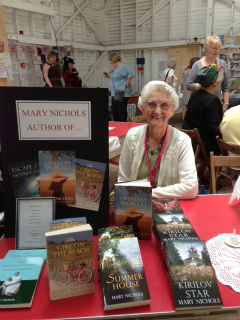

A Day for Writers

Sun, 22/03/2015 - 15:25 — Mary Part of an author’s job is promotion. It could be done on line with blogs, guest blogs, a website, Facebook and/or, twitter. It could be a book launch in a bookshop in which you concentrate on the newly published book, or giving talks to reading and writing groups or the Women’s Institute and other like groups. The whole idea is to persuade people to buy your books in the gentlest and most interesting way you can. It’s a talk not a speech.

Part of an author’s job is promotion. It could be done on line with blogs, guest blogs, a website, Facebook and/or, twitter. It could be a book launch in a bookshop in which you concentrate on the newly published book, or giving talks to reading and writing groups or the Women’s Institute and other like groups. The whole idea is to persuade people to buy your books in the gentlest and most interesting way you can. It’s a talk not a speech.

Sometimes the organiser of the talk will suggest what they want to hear, for example, how you became a writer; writing novels; writing non-fiction; how you organise your day, how you do your research, or (in my case), writing about the Second World War or historical romance for Mills & Boon. They may ask you to suggest something. But you need to research your audience. One size does not fit all. Speaking to an audience can be nerve-racking but if you have prepared your talk well and it’s a subject you are passionate about, then it becomes easier and the more you do it, the more relaxed you feel about it.

Yesterday, I became involved with a Writers’ Day in Ely. It was organised by three local authors, Rosemary Westwell, Hayley Humphrey and Mary McGuire. There were about 40 attendees, enough to fill the meeting room at the library. My Picture shows some of the early arrivals waiting for the event to begin. A series of speakers gave their own slant on writing and being published. My contribution was to offer practical guidance on writing and presenting a novel.

There were opportunities for questions and these were lively and fun. I, for one, am always more comfortable answering questions. Lunch was provided when everyone mingled and asked more questions which showed how alert and interested they were.

The afternoon ended with the Mayor of Ely, Lis Every, presenting the prizes for a short story competition, entries for which had been sent in beforehand. The three judges, of whom I was one, considered thirty-six entries. The standard was generally high and the subjects chosen diverse. The first prize went to In Our Time, by Lisa Woods. This was a gentle story about a widow coming to terms with the loss of her husband and delighting in her grandchildren, a worthy winner.

The day was a great success and there will be another On 17th October. The deadline for the short story is Friday 4th September.

It was great fun talking to everyone, both published and unpublished. I made new friends and perhaps the day might have inspired those who had not yet taken the plunge to go for it. I might even have sold a few books!

A Reluctant Decision

Fri, 30/01/2015 - 17:09 — MaryOccasionally, - only occasionally, thank goodness – it is sensible to abandon a project because it is going nowhere. This week I have reluctantly done that. It is a long story.

Once upon a time, many moons ago, I wrote a story about a brother and sister, Sarah Jane and Billie, who are turned out of their home when their parents die and are forced to go to the workhouse. The workhouse is not a nice place to be in the middle of the nineteenth century. Husbands are separated from wives, mothers from children, brothers from sisters and the regime is harsh. Sarah Jane and Billie are separated as soon as they arrive and from then on their lives follow different routes. Now and again they come within a whisker of being re-united and then fate takes a hand and sets them off in different directions again. The story covered both their lives. When it was finished it was over 250,000 words long. Yes, that’s not a misprint I really did write a quarter of a million words and on an ordinary typewriter not a computer.

No publisher was interested in such a long book, especially by a little known author, so I put it in a drawer and got on with other projects, books that did find publishers. But Sarah Jane and Billie were living, breathing human beings and they clamoured to be let out.

One day, between books, I fetched the weighty typescript out and set to work splitting their stories into two separate books beginning with Sarah Jane. It had umpteen versions before I felt satisfied and the result was The Stubble Field. It was published by Orion Book way back in 1993 twenty years after I first began it. It had a very small print run and was soon sold out, but the publisher declined to reprint (though it was reprinted twice in French). I thought Billie’s story, coming quickly afterwards might encourage them to change their minds and hurried to finish it. All to no avail. Not only did they decline to reprint The Stubble Field, they rejected Billie’s story on the grounds that historical novels were out of favour, no one was buying them. No other publisher would look at a sequel to one published elsewhere. Poor Billie was consigned to the drawer again, in spite of so many people asking me, ‘Whatever happened to Billie?’

Then along came Kindle and ebooks. I seized the opportunity to reissue The Stubble Field under the new title of A Line Through Chevington, and self-published Billie’s story as Promises and Pie Crusts. (along with others of my backlist). They have done reasonably well and attracted a few good reviews and I receive a cheque every month and that is very gratifying.

But there are still people out there who like to hold a printed book in their hands and Promises and Pie Crusts had never been printed, so I hit on the idea of using Amazon’s CreateSpace and print on demand. I didn’t do it all myself, I hasten to add, I had the technical help of my lovely daughter-in-law, Elaine, but then I had another thought. Although it could stand alone as a story, it really needed reading after A Line Through Chevington and that had been out of print for years. So, we set to work on that one too.

And then we discovered we had not done our homework thoroughly enough. Both, in spite of judicious pruning were over 150,000 words long, and Amazon charge by the page. The minimum price for the books was going to be over £12 each! No one would pay that much for a paperback novel, so I was in a dilemma. I did think of splitting each of them into two books to make them cheaper but if someone wanted to read the whole story, they would need to buy all four and that would in the long run be more expensive. Not only that, it would mean more covers and I would have to write some back story into the sequels, meaning more editing. I decided new books were more important and reluctantly decided not to go ahead.

What would you have done?

Both books are still available on Kindle.

Planning a new book

Thu, 09/10/2014 - 08:59 — Mary I am at the planning stage of a new book. The premise has been agreed with the publishers, so I can go ahead. The next stage is to assemble the characters because it is the characters, their actions and reactions that drive the story forward. I can't do any of this until I have decided on their names (even if they are changed later).

I am at the planning stage of a new book. The premise has been agreed with the publishers, so I can go ahead. The next stage is to assemble the characters because it is the characters, their actions and reactions that drive the story forward. I can't do any of this until I have decided on their names (even if they are changed later).

For the hero and heroine I need to know how old they are, their physical attributes, family background, where they live, what they do for a living, character traits, likes, dislikes, beliefs, but most of all what drives them to do what they do.

Once that is established, there is a supporting cast, parents, siblings, lovers, husbands, neighbours, friends and enemies. I might not have all these to start with and some I might discard as unnecessary.

I need the setting, country, town, village, UK or abroad. I might have a real village in mind, but I'll give it a fictitious name, probably near a real town so that I can be more flexible if the plot dictates a change. Sometimes I'll visit places, but I find that they never look or feel as they must have done in the past, so I tend to rely on personal stories and memoirs of people in my chosen era. In the case of my WW2 books, I have my own memories of what it was like to live through it.

Next comes a plot outline and time line of actual historical events which are important to the story which I link together. If there are any unusual weather patterns during this time I make a note of them. I don't want to write about pouring rain if my characters are in the middle of a drought. I must also remember the seasons and how that effects the characters' lives, especially in a farming community.

Then I decide when the story is going to start. It is usually some defining moment in the plot, followed by a little back story of how we arrived there. The scene is in my head, vivid and waiting to be set down. Until that stage is reached, I don't write a word.

I know other authors work in a different way, some start with and idea and a blank page, but that has never worked for me. I don’t stick slavishly to my plot, sometimes my characters dictate otherwise and I usually go along with them because to me they are real people behaving in the way real people would. Forcing them in line rarely works.

The biggest problem is finding a title that everyone agrees on. I can't start without a title so it is given a working title which is almost inevitably changed. I say almost because A Different World was always going to be called that.

What the new book is going to be called I have no idea.

Meeting the readers

Fri, 18/07/2014 - 07:47 — Mary

Another Romantic Novelists' Conference has come and gone. A weekend of talks, discussions, lectures and conversation and good food have sped by. This time there were other events taking place in conjunction with it. Wellington Library, Shropshire was the venue for an afternoon and evening of meet the author, talks, workshops took place of Thursday 10th July

Picture on th left by courtesy of Pia Fenton. Tho Group picture by David Lightfoot.

On Friday we took part in a book fair at Blists Hill Victorian Village at Ironbridge near Telford. A barn at this wonderful museum was given over to historical novelists to display their books and provide information about the times in which they are writing. They ranged from Ancient Rome to World War Two and alternate history.

Many of us dressed up in the appropriate costume and brought artefacts of the times. It was a fun event that we hope demonstrated the diversity of historical writing, all with a romantic flavour, of course. It was a way of bringing the reading public into our gatherings and we hope to repeat something like it at future conferences.

Taking it on the chin

Mon, 30/06/2014 - 09:03 — Mary I asked a few author friends how much store they set by reviews and received mixed replies. Some said they read them and would be put off by a bad review, others said they might read them and ignore them if they liked the sound of a book or if it had been recommended. One or two said they never read them.

I asked a few author friends how much store they set by reviews and received mixed replies. Some said they read them and would be put off by a bad review, others said they might read them and ignore them if they liked the sound of a book or if it had been recommended. One or two said they never read them.

I would by lying if I said I did not enjoy good reviews and I have had my share of those, for which I am grateful. I don't mind criticism, you can’t please all of the people all the time and the bad reviews I take on the chin, shrug my shoulders and carry on, but sometimes the temptation to defend one's brainchild is almost overwhelming. Maybe the reviewer got out of bed on the wrong side, maybe they are naturally grumpy people, maybe the book was the wrong one for them, maybe I hit a chord that upset them. Who knows? They are entitled to their opinion.

I write books set in the second world war, a time I am old enough to remember vividly. When a critic writes that my characters show no emotion when people die or are lost, except shed a few tears and carry on, that was how it was. There was emotion, lots of it, but the legendary British stiff upper lip kept it hidden. You didn’t have time to grieve for long.

The question of illegitimate babies has cropped up more than once too. It happened. It was frowned upon and girls were often sent away to have the child elsewhere, as happened in The Summer House, or beaten and disowned as Louise was in A Different World or isolated from family and friends as in Escape by Moonlight, but illegitimate births were happening more and more often with men going off to fight and making the most of their leave before they went, and many of the men came from abroad and were far from home. Society was becoming a little more tolerant and you did find parents and friends helping out instead of condemning.

Attributing modern ideas and manners to historical characters, is something reviewers often do and then complain that the heroine doesn't stick up for herself.

People did not think or behave in the same way in Georgian or Regency times as they do today or even as they did in Victorian times or the twentieth century. It is fascinating to see how attitudes have changed over the centuries and how women have come into their own, particularly through two world wars, which changed everyone's lives.

I ignore bad reviews in the hope that the good ones more than tip the balance, but I was particularly pleased when one reviewer answered a criticism for me, explaining why my heroine continued in a loveless marriage in the time between the two world wars. You married for better or worse and as it was often said, 'You made your bed, you must lie in it.'

Thank goodness I have no real cause for complaint.

Historical background

Tue, 01/04/2014 - 08:05 — Mary Those who know my books, know that I write mainly in the Regency and World War Two eras, which means research, which I love. Historical facts are one thing, social background another altogether and there are many pitfalls to avoid. Fashions, furnishings, means of transport and communication must be right for the period.

Those who know my books, know that I write mainly in the Regency and World War Two eras, which means research, which I love. Historical facts are one thing, social background another altogether and there are many pitfalls to avoid. Fashions, furnishings, means of transport and communication must be right for the period.

If you are dealing with stage coaches, you need to know how long they take to get from A to B and the route; how often it would stop to change horses; the accommodation available on the way and how much it would cost. Going by the mail, which was more comfortable and faster, was more expensive and going post chaise meant using your own coach but having horses posted along the way and that was really only for the very rich. You could of course use you own horses the whole way but that was extremely slow because they had to be rested so often. There was always the carrier's cart, used mostly for delivering goods, for those who could not afford to go by coach and that was uncomfortable and very slow.

You wouldn’t get on a train before the middle of the 19th Century and then it would be an innovation, frightening or exhilarating, according to your age and temperament, and very dirty. Motor cars were rare before the Great War and not all that common between the wars and they didn't have heaters, so making a car journey in winter meant wrapping up warm.

Very few people had telephones before the first world war and working class homes didn’t have them in the second world war either. You would go to a telephone box to make a call. If the recipient didn't have a phone you would ring a neighbour who did and leave a message. You could send a telegram, but during the war the sight of a telegraph boy coming up the path often heralded bad news as that was the way the authorities let next of kin know that their loved one was a casualty.

Taboos and morals, too, change over the years. What is right for one period would be frowned on in another. Sex and having babies out of wedlock, for instance. It was considered a disgrace right up to and including the Second World War and for some time after that and girls who transgressed were often turned out of their homes by furious parents or made to marry the man whether they wanted to or not. The alternative, if the parents could manage it, was to send the girl away to have the child in secret when it was immediately sent away for adoption. A week or two later the mother would be sent home and expected to get on with her life as if nothing had happened. Nor would she be told where her child had gone or anything about the adoption.

A century before that, girls were never left alone in the company of a man and were always chaperoned, which must have been inhibiting. But somehow they managed to find husbands, or one was found for them. It may seem strange to modern readers, who would not hesitate to break off an engagement if they realised the love they had hoped for was missing, but in Regency times, the social mores were different. Love was not the only, or even the main, reason for marrying. Title, wealth, status, the wishes of one's family and the need to keep an unbroken hierarchy, all played a part. Divorce was only for the very wealthy and required an Act of Parliament, and an engagement was a solemn undertaking. A lady might brave the censure of Society and break her promise to marry, but a gentleman never could. It was a dishonourable thing to do and laid him open to being shunned by Society as a man who could not be trusted to keep his word.

Dialogue must reflect the times without becoming stilted. If we stuck slavishly to the way people spoke in Medieval, or even Regency times, for instance, it would become almost unreadable. You need to give a taste of the era in the way people speak but not overdo it. The same could be said of dialect. Slang must be used with caution because it is so volatile. Georgette Heyer used a lot of slang but it was part of the charm of her books. Whether it was always entirely accurate is another matter.

But however thorough the research, it is important not to give in to the temptation to put it into the book willy-nilly just to prove you know it. It should be like an iceberg; nine tenths below the surface, one tenth visible. It is there to set the scene, to put the period and surroundings into perspective. You use only what is necessary to take the story forward. And if you make a mistake, you can be sure someone will point it out to you!

Two books just out illustrate this. A Different World set in WW2 and Scandal at Greystone Manor which is a regency.