Blogs

Comments

Fri, 28/02/2014 - 15:29 — MaryI love having genuine comments to my blogs and will happily reply to them, but I receive hundreds everyday which are pure spam. These are filtered by the moderator and I have periodically to delete them. I have also been told that anyone who ticks to be informed when new comments are posted, ends up receiving the spam as well (before I can delete it). I am very sorry about this, but all I can do is to suggest you don't ask for new comments to be sent automatically but look at the site occasionally to see if there is anything that interests you and on which you may wish to comment. In the meantime I will try and make sure the rubbish is quickly deleted Genuine comments, will of course be posted and replied to.

Bletchley Park

Sun, 23/02/2014 - 11:04 — MaryLast Thursday, in the interests of research, I visited Bletchley Park. I should think most people have heard of Bletchley Park and the secret work it did cracking the enigma code.

Bletchley Park was simply a country mansion when it was first taken over to be the home of the Government Code and Cypher School in 1939. Here a handful of very gifted and very clever people began the task of cracking the code. A fiendishly difficult task. They were given a head start by the Poles who had cracked an early version before the war and shared what they had learned with Britain and France.

A code, so we are told in the many exhibits, hides the meaning of a message by replacing a word or phrase with another character or set of characters. A cypher replaces each letter in the original message with another letter. Enigma was a cypher system. The machine did not transmit messages. They were first encyphered by a clerk typing each letter into an enigma keyboard according to a series of instructions which came up on a lighted display as the encyphered letter. This had to be written down and transmitted in Morse code by radio and someone at the receiving end would feed the code into another enigma machine set up in exactly the same way as the sender's, which decrypted it. It was these Morse signals that were picked up by listening stations in England. Some were intercepted at Bletchley Park itself, but most were brought from outlying stations by motor cyclists who were out in all weathers. The task of the code breakers was to turn these messages into readable German.

A code, so we are told in the many exhibits, hides the meaning of a message by replacing a word or phrase with another character or set of characters. A cypher replaces each letter in the original message with another letter. Enigma was a cypher system. The machine did not transmit messages. They were first encyphered by a clerk typing each letter into an enigma keyboard according to a series of instructions which came up on a lighted display as the encyphered letter. This had to be written down and transmitted in Morse code by radio and someone at the receiving end would feed the code into another enigma machine set up in exactly the same way as the sender's, which decrypted it. It was these Morse signals that were picked up by listening stations in England. Some were intercepted at Bletchley Park itself, but most were brought from outlying stations by motor cyclists who were out in all weathers. The task of the code breakers was to turn these messages into readable German.

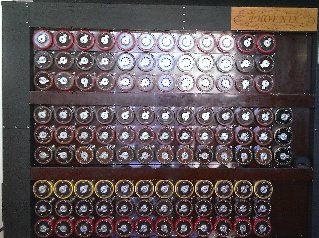

The secret was in the setting up of the enigma machines. Three rotors, marked with the letters of the alphabet, had to be selected from a set of five. The selected rotors had to be located in the machine in the correct order; there were six possible ways to do this. Then the rotors had to be set to their starting positions; there were 26 x 26 x 26 or 17,576 possible way to do this. Then 10 pairs of letters had to be connected on the plug board. The configurations of the machine allowed 158 million, million, million ways. The picture on the right is of the front of the machine.

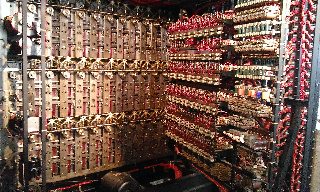

Seems impossible, doesn’t it? It was done by a process of elimination and could not have been done at all without the use of cribs. These were parts of the message which could be guessed at, things like call signs, dates, times, length of message, stock phrases like 'nothing to report' and the German operators being careless and making mistakes. Machines called 'bombes' were developed by Alan Turing and Gordon Welchman to help with the checking and you can see one of these at work at Bletchley. It is amazingly complicated and involves sets of drums, each representing a rotor on the enigma, and at the back a mass of wires and connections. When working, they were hot and very noisy and were operated by WRNS (Women's Royal Naval Service) who were standing their whole shift on concrete floors. Their work was painstaking and fiddly and involved setting the machine up according to a menu obtained from cribs. But the bombes could go through all 17,576 possible positions in 30 minutes.

If the menu worked the machine would stop and those settings were sent to the code breakers, who would apply them to a Type X machine set up like an enigma. If it was viable, plain German text would come up on the display in groups of five letters. That was sent to the translators and afterwards disseminated to whoever needed to know. But few of the recipients knew where the information had come from and were told 'from a reliable source' or made to look like the report of a spy. Sometimes they didn't believe it. But this wasn't a one-off affair, the Germans changed the setting every 24 hours at midnight and the whole process would have to start again. The work went on night and day, 365 days of the year, the aim being to crack the day's code while the information in it was still useful.

If the menu worked the machine would stop and those settings were sent to the code breakers, who would apply them to a Type X machine set up like an enigma. If it was viable, plain German text would come up on the display in groups of five letters. That was sent to the translators and afterwards disseminated to whoever needed to know. But few of the recipients knew where the information had come from and were told 'from a reliable source' or made to look like the report of a spy. Sometimes they didn't believe it. But this wasn't a one-off affair, the Germans changed the setting every 24 hours at midnight and the whole process would have to start again. The work went on night and day, 365 days of the year, the aim being to crack the day's code while the information in it was still useful.

The picture on the left is the back of a bombe machine.

There were also several different types of encrypting machine and the settings for the navy, were different from those of the army, the air force and the secret service. There were also Italian and Japanese machines. And the German High Command had an even more complex one, called Lorenz. Later, a very clever man called Tommy Flowers constructed the Colossus, said to be the forerunner of the modern computer. Most of us can remember the old main frames that took up so much space in offices when they first came about. Now almost everything is computerised and those of us who are not technically savvy have had to learn to use the technology.

I had already read several books on the subject of Bletchley Park and the enigma, but going round the ground floor of the mansion and round the huts that have been restored certainly gave me an insight into the work that went on there and the security that protected it.

Towards the end of the war, around ten thousand people were working at BP and its scattered outposts. Some were in the services, some were civilians, but rank and uniform counted for very little. Each had his or her allotted task and, apart from the people they worked with, had no idea what others were doing. Mail was sent all over the country by motor cycle to be posted so that Bletchley was never identified. With so many people of both sexes working in such a close atmosphere, romance was inevitable and produced several weddings. There is one story that a couple who married after the war did not know that each had been working at Bletchley Park until the secret came out in the seventies. Ten thousand people keeping such a vast secret is difficult to comprehend nowadays, but keep it they did. And the work that went on there is said to have shortened the war by at least two years.

Taking the plunge

Wed, 15/01/2014 - 16:19 — Mary Here is the last of my monthly blogs for the Australian site: writinghistoricalnovels.com I hope those who have been following them, have found them interesting. I certainly enjoyed doing them.

Here is the last of my monthly blogs for the Australian site: writinghistoricalnovels.com I hope those who have been following them, have found them interesting. I certainly enjoyed doing them.

They say you should write about what you know, especially when you are feeling your way as a writer, but that can be dreadfully restricting and if you did that, you would never write books with historical backgrounds. Think what opportunities you would be missing! The story is the thing and as long as your research is thorough, there’s no reason why you can’t attempt something a little more adventurous.

I’ve always been fascinated by Russian history, ever since I read Tolstoy’s War and Peace and Anna Karenina, and Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov and Crime and Punishment as a schoolgirl - in English, I hasten to add. Then later when Dr Zhivago was made into a film it renewed my interest, especially in the Revolution and the terrible fate of the Tsar and his family and the rumours that the Grand Duchess Anastasia had survived. A film was made about it and for a long time it was believed, but this has since been disproved with DNA tests. It was a time of such upheaval that people simply disappeared. The idea for a book simmered in my mind for a long time and though I planned it out, I hesitated to begin writing for fear of biting off more than I could chew.

When I told my family about it, I began receiving books about Russia for birthday and Christmas presents. That set me collecting books to help with my research, until I had dozens of them. The more I read, the more I became immersed in the history and eventually I couldn’t put it off any longer and THE KIRILOV STAR was born

My aristocratic family, distant relatives of the Tsar, are separated when trying to leave Russia during the civil war in 1920. The only survivor is four-year-old Lydia Kirillova, too young and too traumatised to tell anyone what happened and where she comes from. She knows her name but the only other clue to her identity is a fabulous jewel sewn into her petticoat. She is taken to a British diplomat who has been instructed to oversee the evacuation of the refugees and then leave himself. He is left wondering what to do with her.

He could send her to a Russian orphanage, but they were notoriously dreadful places and for someone who appears to be of aristocratic stock, it would be worse. He and his wife are childless, something they both regret, could Lydia fill that gap? He could give her a good life, but would his wife accept her? Would Lydia later blame him for taking her from her homeland?

He decides to risk it and Lydia grows up in the privileged background of a stately home and seems content. But Kolya, another Russian émigré, sows the seeds of her discontent and persuades her to marry him and go back to Russia with him to look for her real parents. It is the biggest mistake of her life. Russia under Stalin is a dangerous place for an ex-aristocrat to be. Her husband leaves her for another woman, taking their son, Yuri, with him and she is trying to track him down when the second world war breaks out and her situation becomes desperate. She has left a good home and loving family to chase a dream which turns into a nightmare. She is forced to abandon her search and return to England and only much later when Stalin is dead and it becomes easier to travel is she able to resume her search for her son, helped by the man who has always been in the background of her life and has loved her for years. But when Yuri is finally found, the years apart and the different cultures are not so easy to bridge.

Having written it I wanted someone who was familiar with the country and the times to look at it before I submitted it to my publisher. And here I was lucky. Two of the books I had used for my research were Moscow 1941 and Across the Moscow River, both by Sir Rodric Braithwaite who was British Ambassador to Moscow from 1988 to 1992 and I wrote to him, asking if he would take a look at the typescript. It was a long shot but to my delight he agreed to do so and, besides making some very pertinent comments for which I was very grateful, told me my research had been very thorough and he had no quarrel with it. It just goes to show you should never be afraid to be adventurous. Most people I have approached with queries have been happy to oblige. And taking a chance paid off.

The Kirilov Star was given a Singles Titles Reviewers' Choice Award for 2012 by Catanetwork Reviewers.

Building Family Anecdotes into a novel

Tue, 10/12/2013 - 15:57 — MaryThis is the eleventh of my monthly blogs for writinghistoricalnovels.com.

If you are writing historical fiction about a time within living memory, then talk to people who were there and ask questions. What can our parents and grandparents tell us about life as it was? I think it is a pity we don’t do this more often, even if we aren’t writing a book about it. My husband is very elderly and his short term memory is patchy but he remembers his childhood and war years very clearly.

If you are writing historical fiction about a time within living memory, then talk to people who were there and ask questions. What can our parents and grandparents tell us about life as it was? I think it is a pity we don’t do this more often, even if we aren’t writing a book about it. My husband is very elderly and his short term memory is patchy but he remembers his childhood and war years very clearly.

Over the sixty-three years of our marriage, I have heard his wartime stories many times, but though they might vary in detail as he remembers something new, they are consistent in the story they tell. Two things stand out: his adventures on D-Day and being wounded after he was parachuted into Germany later on in the war. Crossing a ditch he jumped on a mine and was blown sky high, according to witnesses; he doesn’t remember it. He woke up in hospital in England with traumatic loss of memory. Luckily for him it came back after a few days. Stories like that are tucked away in my mind until suddenly they resurface when something triggers them off. It was only recently I began to think of loss of memory as a theme for a book and what better background than the Second World War?

I tried to imagine what it would be like not to remember your own name, where you come from, even whether you are married or not. It must surely affect everything you do and say and think and you would be forever niggling at it, trying to bring it back I did some research about loss of memory which was mostly medical based and way over my head, but I did learn that it is a myth that loss of memory caused by a blow on the head would be cured by another blow. It is more likely to make it worse. The most likely scenario for the return of memory would be if the person concerned was put in a similar situation to the one that caused the loss in the first place.

When war breaks out, Julie Walker, not long married, is left to cope with wartime London and bring up her baby without Harry, her husband, who has joined the RAF. She is caught out in an air raid and directed to a shelter which receives a direct hit. Pulled out alive but injured, she is taken to hospital, but she has lost her memory. She cannot tell them who she is, where she lives or even if she has a family. (I had her pawn her wedding ring to buy black market food for her baby, so it would be assumed she was single.) She is given a new name and must make a life for herself as Eve Seaton. Harry, who believes his wife and child have been killed, must put his grief behind him and get on with his part in the war as a radio operator in a bomber crew. Julie is disturbed by flashes of memory, little things that confuse her more than enlighten her and she wonders what dreadful secret her loss of memory is hiding. When it eventually comes back she is left with a dilemma. Is she Julie Walker, married to Harry, or is she Eve Seaton, a sergeant in the WAAF, engaged to Alec Kilby? And who is buried in the grave alongside her son?

Alec is in the parachute regiment and I called on the experiences of my husband for Alec’s training and his D-Day experiences. I still had lots of research to do: WAAF training and the jobs they were likely to be called on to do, RAF bomber command and wartime factory work. Then I had to get the timeline of real events and fictional events to bond. The result was The Girl on the Beach, published by Allison and Busby in 2012.

You will find more details on my website. Click on All Mary's Books>Saga/Mainstream

***

Collective noun for a group of romantic novelists.

Fri, 06/12/2013 - 16:38 — Mary

Village brickmaking

Sun, 01/12/2013 - 11:40 — Mary

Another story about my grandmother's life in the Norfolk village of Necton.

Another story about my grandmother's life in the Norfolk village of Necton.

My grandmother's mother died a fortnight after giving birth to her fourth daughter in 1890, probably of puerperal fever and Eliza, at eight, the oldest of the girls, found herself trying to look after her father and younger sisters. In her own words, she ‘didn't think much to that'. Her father employed a housekeeper for a time, but in December 1891 he married again. The poor woman was probably trying to do her best for the young family, but Eliza saw her as a usurper and when another girl, Rose Ellen, was born in June the following year, she decided to run away from home. Taking nothing with her, she walked the four miles to Necton to put her case to Grandmother Brown.

Her grandfather was a brickmaker and had his home and premises on the Dereham Road. He agreed she could stay with them on condition, she earned her keep working in the brickyard and they would give her a shilling a week for herself. She never went to school again. Her grandparents must have told her that if anyone came asking questions, she was to say she was thirteen and she was to stick to that however hard she was pressed because otherwise she would be sent back to her father and everyone would be in dire trouble. She must have been a very young looking thirteen, and one can only suppose that no attendance officer appeared in those early years, or he would surely have been suspicious. Hard work and better food soon put some flesh on her as she was forced to leave her childhood behind and grow up. Childhood games were forgotten as she set to work, learning the business of brickmaking.

Before the coming of the railways, most small towns and large villages had brickworks, often as a sideline to farming, based at the nearest pit where suitable clay could be extracted. Bricks were always wanted for dwellings, farm buildings, breweries, maltings, warehouses and suchlike, there was a steady demand and brickmaking a fairly sure means of making a living. The finished bricks were transported to their destination by horse and cart and so it was sensible for builders to buy locally and keep transport costs to a minimum.

The advent of railways meant the bricks still had to be taken to the railway terminal in the time-honoured way, but once there, they could be sent almost anywhere. This was both a curse and a blessing. In the late nineteenth century, there was a huge demand as the entrepreneurial Victorians embarked on expansion, which in its turn fuelled a demand for bricks for churches, chapels, schools, hospitals, town halls, public houses and railway stations. For a time brickmaking flourished.

The Necton brickworks occupied three acres of land not far from the house and close to a large clay pit. As soon as breakfast was over, Eliza put on a huge sacking apron that came down to her boots, covered her hair with a mob cap and accompanied her menfolk down to the pit to help shift the clay, known as ‘gault’, as it was dug from the pit and piled up for the winter frosts to break up.

Digging was seasonal, starting in autumn and continuing until February. The piles of clay were turned periodically and this must have been a backbreaking job. I doubt whether Eliza was expected to do this, but there were other things she could do. The actual brickmaking began in the spring when the clay was 'puddled', which meant wetting it and stirring it to make it like dough. In earlier times it was done by workers treading it and turning it with spades but by the time Eliza was working, it was put in a pug mill, a kind of barrel with an upright shaft down the middle with sharp blades sticking out of it, rather like an oversized dough mixer. It was worked by a horse harnessed to a beam attached to the shaft which was led round and round to turn the blades.

Other things were added to get rid of impurities and make exactly the right kind of mix. Every brickmaker had his own ideas about what should go in; it was like making a giant cake with a secret recipe. It was why some bricks were a different colour from others, why some were harder than others, some more porous. Experienced brickmakers could tell where a brick came from just by look and feel. The final mixture was shaped into bricks by a machine that cut and ground the clay and then forced it out through a hole the shape of a brick, so it came out like toothpaste. This was cut into separate bricks by wires on a frame. The brick was made the size of a man's hand so that he could pick it up easily.

The clay was pressed into a mould and leveled off using a stick called a strike. The bricks that came out of the mould were called green bricks. They were spread out on a flat wheelbarrow and taken to the drying ground where they were arranged in a herringbone pattern on wooden racks, row on row, up to ten feet high. The stack was called a hack and the bricks were left like that to 'cure' meaning dry enough to be fired. The firing was started in April and went on all summer until all the clay had been used.

The kiln was like a big oven with holes along the bottom for the fuel and an opening opposite the holes called a wicket. There were more holes at the top which controlled the amount of air to the fire, which was lit at the bottom, so that the heat gradually drew up through the bricks. Stacking the bricks in the kiln was a skilled job, making sure not too many were spoiled by under or over burning. Early fuel was ling (heather), furze (gorse) or bracken, but by my grandmother’s time they were using coal, though furze and bracken were still used to light the fire and it was one of her tasks to collect it. The fire was left to burn slowly for three days and then the fire holes were opened and the top of the kiln removed to let in more air in and make it burn faster. After two or three days fast burning, all the holes were blocked up and the fire left burn itself out. The bricks had to be left to cool for another week before they could be handled and removed and the kiln made ready for the next batch.

Her work was dirty and physically demanding, but she stuck it out, fetching kindling, carrying green bricks to the kiln and fired bricks to the stacks to be sent to their customers, throwing out those that were too burned and those that were not burned enough, stacking bricks, and leading the horse in its endless perambulation, working from six in the morning to six in the evening. Working outside in the summer was one thing, working outside in the winter, when feet became numb and hands chapped with being continually wet, was quite another, but Eliza, stubbornly determined, would not complain. She became strong and sturdy and independent, traits that carried her throughout her long life.

The brickmakers were proud of their skills and they used to demonstrate this in the building of their own homes. My picture shows the house that my great great grandparents lived in. It was originally two cottages but as the family expanded they took over both homes. It clearly shows how bricks can be used to embellish even a humble dwelling and it is now listed. In the alcove in the middle is a statue of a small boy holding a bird's nest. He only has one arm and the story goes that he fell while climbing a tree to reach the nest and broke his arm so badly it had to be amputated. Who the boy was, I have no idea, but according to my grandmother it was made by the brickmakers as a salutary lesson not to steal from the birds.

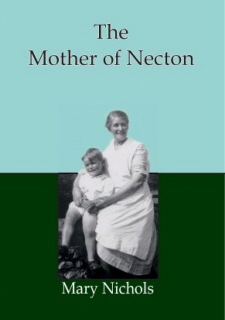

If you would like to know more, it's in my biography of Eliza's life, THE MOTHER OF NECTON, ISBN: 978 1 904006 48 0, published by The Larks Press

Writing Historical novels for Mills and Boon.

Tue, 29/10/2013 - 08:38 — MaryThis is the tenth of my blogs for writinghistoical novels.com which you can see at:http://writinghistoricalnovels.com/2013/10/25/writing-historical-romance-novels-for-mills-boon-by-mary-nichols/

In the middle of the 1980s I was having a few very slight contemporary novels published and getting nowhere with my historical sagas, so I thought I would try Mills & Boon. Rumour has it that Mills & Boon authors earn pots of money for penning books that are an easy option. Nothing could be further from the truth. They are not easy and only a very few of their authors earn anything like pots of money.

In the middle of the 1980s I was having a few very slight contemporary novels published and getting nowhere with my historical sagas, so I thought I would try Mills & Boon. Rumour has it that Mills & Boon authors earn pots of money for penning books that are an easy option. Nothing could be further from the truth. They are not easy and only a very few of their authors earn anything like pots of money.

Mills & Boon is the undisputed leader of romance fiction. As a global company Harlequin, the parent company, sells 130 million books a year, in 114 countries and 34 languages. In the UK one book is sold every 4 seconds. There are one and a half million regular readers and fifty million books are borrowed each year from UK libraries. There are 1200 authors worldwide, acquired through 3 commissioning offices. The Richmond office in the UK works with approximately 200 authors.

The company was originally launched as a general fiction publisher. During 1909, their first years of trading, 123 contracts were signed using well-known authors. But Charles Boon wanted to encourage new authors and in 1912, 1,000 manuscripts were sent in, 95% from unknown authors. Of those only six were published. It is a state of affairs still true today, so I was very lucky that my first submission was accepted. In 1957, the Canadian publisher, Harlequin Books, began publishing Mills & Boon titles and in 1971 the companies merged and became Harlequin Mills & Boon.

Their books are easily identified by the covers, which has been both its success and its bane. It is why people think they are all alike, without ever having read one, which is untrue and very unfair.

The historicals are longer than the modern stories and give the writer more scope to develop the background and story. Because they are first and foremost love stories, the hero must be someone we could all fall for, handsome, sometimes hard on the outside but soft inside. The heroine, if not beautiful, must be attractive and feisty, with a mind of her own. They both come into the story with 'baggage', that is some problem or difficulty that prevents them getting together. Everything is geared to the outcome of that. It is how it is reached that makes the story though there must be a doubt in the reader's mind about how it will all turn out. Happy endings are a must! Apart from that, the author is free to tell the story in her own way.

Historical background must be accurate though it must never take over the story. And fashions, furnishings and social taboos must be borne in mind. Dialogue must reflect the times without becoming stilted, all of which is true of any historical novel, and it is better to focus on a single historical event that try to cover several.

For instance: In A Bachelor Duke the theme was Wellington's triumphant return from the Napoleonic Wars. In Working Man, Society Bride it was the building of the railways. In A Desirable Husband it was the controversy surrounding the building of the Crystal Palace when the upper class residents of Kensington opposed it on the grounds it would bring in the riff-raff and the value of their properties would fall. In Lady Lavinia's Match it was George IV's endeavour to divorce Queen Caroline and prevent her being crowned with him. In The Hemingford Scandal it was the Duke of York's mistress selling favours on his behalf and causing a national scandal. It’s funny how history has a way of repeating itself.

Last year I finished a series of linked books about how law and order was (or was not) kept in Georgian times. There was no regular police force and anyone who had been the victim of a crime had to find his own way of bringing the perpetrators to justice. My heroes, all honest gentlemen of rank, belong to the Society for the Discovery and Apprehending of Criminals, known also as the Piccadilly Gentleman's Club, who work to bring criminals to justice. In solving mysteries, each finds the love of his life. There have been six so far: The Captain’s Mysterious Lady, (shortlisted for The Love Story of the Year 2010) The Viscount’s Unconventional Bride, Lord Portman’s Troublesome Wife, Sir Ashley’s Mettlesome Match, The Captain’s Kidnapped Beauty and the latest. In the Commorodre's hands.

Each of my books is published in hardback, paperback and large print, and also as e-books. They have been translated into French, German, Spanish, Italian, Swedish, Finnish, Greek, Polish and Russian and also sold in America and Australia.

Find them all on www.marynichols.co.uk or www.millsandboon.co.uk

Plot and Character in Historical Novels

Mon, 07/10/2013 - 15:12 — MaryThis is the seventh of my blogs forwww. writinghistoricalnovels.com put together by Steve Rossiter.

A good plot and believable characters are a must for any book, no less for the historical novel than any other, perhaps especially for the historical because the temptation to concentrate on the history to the detriment of the story must be overcome. Readers don’t want a history lesson, they want a good story and if, in the process, they learn something new of times past, that is all to the good.

A good plot and believable characters are a must for any book, no less for the historical novel than any other, perhaps especially for the historical because the temptation to concentrate on the history to the detriment of the story must be overcome. Readers don’t want a history lesson, they want a good story and if, in the process, they learn something new of times past, that is all to the good.

Once I have decided on my theme, I make a careful plan of where the story is going, write biographical notes of all the important characters, their names, physical characteristics, their character traits, their motivation, the chronology of events, both real and imagined. Slotting the two together is where the research comes in. By the time I am halfway through writing the book, something happens that I haven’t allowed for and I have to think again. About three quarters of the way through I’m so far into the story that it takes over. But without that original plan to get me started, I’d be lost.

For me, the characters, their actions and reactions are what drives the story. The reader needs to be with them all the way, to identify with their problems, sympathise when they are down, share their joy when they are up, worry with them when fate turns against them, celebrate when things go right, feel their emotions with them. Even the bad characters. I don’t have really wicked characters in my books because I like to explore the reasons why they are bad and perhaps find some redeeming feature. If what is happening to my characters is emotionally challenging, then this, I hope, comes over in my writing. The reader needs to believe that these are real people, acting and speaking as real people would, even if they find themselves in extraordinary situations. Characters do not need to come to the book fully rounded, but grow and develop as the story progresses, so that at the end they have been subtly, or perhaps not-so-subtly, changed by their experiences.

But in developing characters, the fact that the book is historical needs to be borne in mind. How people acted and reacted to a given situation might be very different in your chosen era from the way they might react in today’s world. You cannot put modern values in the heads of people of two hundred years ago, (unless the whole thing is a spoof). What you want your characters to go through and how you want them to behave, might very well influence your decision about the era you want to set the book in.

For instance, I set THE FOUNTAIN between the two world wars. George Kennett is a young man determined to make his mark in the East Anglian town in which he lives and is not above a bit of skulduggery to achieve it. He is a builder and breaks all the rules of ethical behaviour, secretly setting up rival companies in order to get Council contracts and destroying genuine rivals. It couldn’t happen in today’s world with all the safeguards we now have or, if it did, would soon be exposed. His wife, Barbara, is a talented artist whose talent and personality is being quashed by her domineering husband. She is expected to collude in his nefarious dealings. That too, is unlikely to happen nowadays; no woman worth her salt would comply. Barbara might, by modern standards, seem weak, but she was a woman of her time, and she does eventually rebel. It could not have been set any later, when women became more independent. Any earlier and I would have missed out on the frenzy of building after WW1 to provide ‘homes fit for heroes’. It really could not have been set in any other time.

The Woman You sent for.

Sun, 22/09/2013 - 09:27 — Mary In my last blog I wrote about my childhood visits to my grandparents in Necton, Norfolk where my grandmother was the village nurse and midwife, the 'woman you sent for' in the parlance of the times. She was not unique in what she did. Almost every community, in towns, cities and villages all over the country had such a one and had had since time immemorial.

In my last blog I wrote about my childhood visits to my grandparents in Necton, Norfolk where my grandmother was the village nurse and midwife, the 'woman you sent for' in the parlance of the times. She was not unique in what she did. Almost every community, in towns, cities and villages all over the country had such a one and had had since time immemorial.

No one could remember, least of all Grandma herself, when she had first gone to a sick bed, or which had been her first confinement, but it is a fairly safe bet it was a neighbour who needed help. Most likely it was one of her friends, knowing how good she had been when her own baby daughter had been very ill and they would have known she had assisted at the removal of my Uncle Arthur’s tonsils on the kitchen table when he was a toddler and hadn’t balked at the sight of blood. However she got started, the word soon spread that she was competent, willing and cheerful and, besides that, didn’t charge the earth, and before long she was in great demand. Live births, still births, easy births and difficult ones, boys, girls and twins; they were all part of a day’s - or a night’s - work for her.

The father or an older child would come down the Drift to fetch her and, if it was the middle of the night, would throw pebbles at her bedroom window. When Grandad got up and put his head out, he would be greeted with, ‘Mr Ong, will you ask Mrs Ong to come’ On one occasion, the urgency was stressed by the added, ‘She be hully diluted.’, meaning fully dilated, and Eliza would dress and go. Over her dress she wore a sparkling white apron, which she pinned up at the corners to keep the inside pristine until she arrived at her destination. She carried a black bag in the basket of her bicycle into which she put the things she might need: swabs, disinfectant, mild painkillers. They did not have analgesics in those early days and none were expected. The mother-to-be would have been given a list of things to have ready: torn up sheets, old newspapers, boiled water, a small bath, carbolic soap and the baby's crib or a suitable drawer with some clothes to dress the infant in. My grandmother would duplicate some of these in her bag in case they were not ready.

Grandma never refused to attend, even when she knew she would not be paid. In any case she had no fixed rate of payment. When her patients asked, sometimes diffidently, what they owed, she would say, ‘Give me what you can afford.’ She would be offered a shilling, half a crown, perhaps ten shillings, and occasionally, but not often, a whole pound, and that would probably be for twins. Sometimes she didn’t receive any money at all, but something from the garden or an ornament of some kind. When the family was large and she went year after year, the mother would sometimes miss paying her one year and pay double the next, when perhaps her circumstances had improved.

A couple of her notebooks have survived in which she wrote down the name of the patient and in the case of a birth, the sex of the infant, the date and the payment she received. This little book covers the years 1925 and 1926 and lists some 44 cases, including four sets of twins and one still birth. The most she was paid in those years was £1.7.6d (£1.371/2) for delivering a baby girl, but usually it was ten shillings (50p), and sometimes as little as one shilling and sixpence. One entry had a dash beside it, which probably meant she worked for nothing. On another tiny scrap of paper which is much older and gnawed by mice, she listed ten births in three months, none of them in her home village, so it seems she kept a separate record for those which took place outside the village. If you asked her why she did it, she would shrug her shoulders and quote:

Do the work that’s nearest

Though it’s dull at whiles

Helping, when you meet them,

Lame dogs over stiles.

My grandmother’s life seemed full of lame dogs and she was forever helping them over stiles, nor did she have to go out of her way to find them. There was hardly a family in the village untouched by her ministrations, either at confinement, convalescence, illness, injury or death; they all knew her capable manner and gentle touch. She became known as the Mother of Necton, uninfluenced by the machinations of the nursing world about her which was striving to do away with the unqualified midwife.

At the beginning of the century, the uncertificated woman who served village community in this way, was referred to as the handywoman or ‘the woman you sent for’. If you were lucky, she was clean and knowledgeable and she could soon tell if it would be necessary for a doctor to attend. You only sent for the doctor when you were ill and childbirth was not an illness. Besides, doctors cost money and the village midwife charged only a minimal fee. She was as necessary to village life in those early days as the blacksmith, the miller and the horse doctor.

They were often derided as Sarah Gamps, after Dickens’s character in Martin Chuzzlewit, by those lucky enough to have been able to qualify, but that was unfair on many of them. Certainly no one could have been more careful or caring than my grandmother, whose standard of cleanliness was very high indeed.

As early as 1859, William Rathbone of Liverpool had recognised the need for nurses to administer to poor people in their homes and began, with the aid of no less a person than Florence Nightingale, to organise a band of ladies to do that. They had to be ‘ladies’ as opposed to women, because only ‘ladies’ were supposed to have the intellect to understand the task on hand and instruct poor patients, who would be more likely to obey them than one of their own class and it was believed that only ‘ladies’ had the necessary time to devote to it.

Later, The Midwife’s Institute, afterwards to become The Royal College of Midwives, was been founded to ensure that all women, whatever their status, had access to a qualified midwife and doctor. It wanted to stamp out the Sarah Gamps, believing them to be dirty and ignorant and doing more harm than good, even if well-meaning. In some cases, this was undoubtedly true, but like all sweeping generalisations, it ignored the dedicated, experienced midwife who had been doing the job for years, and who was, in many cases, the only source of help to some women, mainly because qualified midwives had to be paid commensurate with their status, but also because they were not often on the spot in rural areas. The scheme was dogged by administrative wrangles; what training the nurse should have; what she should wear; whether she should have a donkey and cart, a pony and trap, or should be provided with a bicycle to get about her district; what she should be paid and how the money was to be found; whether she should live in a house provided for her or have a living out allowance; what her duties should and should not entail. ‘A lot o’ squit,’ Grandma said. 'You just hatta get on with the job and do your best.’

In 1902, a little before my grandmother began practising, the first Midwives Act had set up the Central Midwives Board to regulate training and examinations and issue or cancel certificates. Local Supervisory Authorities were employed to keep a list of practising midwives in their area, ensuring they knew the regulations. Their remit also included investigating malpractice and where necessary suspending midwives from working in the interests of hygiene and preventing infection. Puerperal infection was the scourge of childbirth in those early days and many women died of it, even after a successful delivery. My Grandmother's own mother had died of it.

Three years later, the first Roll of Midwives was published. It contained the names of those who already had a midwifery qualification from a recognised body or hospital and those who passed a CMB examination. Because their numbers were small and they were mostly concentrated in towns, the list also contained the names of those women of good character who had been in practice for at least a year and whose competence was vouchsafed by the local general practitioner. These were called ‘bona fide’ midwives. Unfortunately there are no records of these women and so I do not know if my grandmother was one of them. From then on, no one could call herself a midwife unless she had a certificate. The ‘woman you sent for’ was supposed to ‘assist’, by doing the washing and housework and looking after the rest of the family, leaving the midwife free to attend to the patient. This did not work either; there were too few certified midwives to go round and the country people still preferred their old methods.

In 1910 the government decreed that women who were not certificated could not attend a childbirth, ‘habitually and for gain’, except under the direction of a medical practitioner. Patients often engaged a doctor whom they knew would be willing to work with local handywoman because he would accept a low fee, knowing he would not be called except in an emergency. All of this washed over the head of my grandmother, who had a family of her own to look after and could not have left home to do the required training. Besides, though far from unintelligent, her schooling had been such that she would not have coped with the theoretical side of it or the written examination. Grandma had two tutors; her own experience of life and the instruction of the doctors with whom she worked and who trusted her implicitly and recommended her to their patients, even when there was a qualified midwife available.

‘If we saw Granny Ong trotting up the road carrying her bag, we would look at each other and say, “So and so must be going to have her baby.”’ One of her friends told me. ‘And a little while later, we would see her come back and we’d call out, “Is she all right? What did she have?” Granny Ong would smile and say, “A little boy, both doing well.” And on she’d go. Or it might be a girl, or twins. But she never said anything else, not about the case. That was confidential and one thing you could be sure of with Mrs Ong, was that she would keep a confidence.’

‘If we saw Granny Ong trotting up the road carrying her bag, we would look at each other and say, “So and so must be going to have her baby.”’ One of her friends told me. ‘And a little while later, we would see her come back and we’d call out, “Is she all right? What did she have?” Granny Ong would smile and say, “A little boy, both doing well.” And on she’d go. Or it might be a girl, or twins. But she never said anything else, not about the case. That was confidential and one thing you could be sure of with Mrs Ong, was that she would keep a confidence.’Grandma could hold her tongue, could smile secretly to herself, knowing the truth and not feel the need to broadcast the fact which is a virtue not many of us have. She was an ideal confidante, a secret told to her remained a secret; she could keep ‘squat’. She must have known all sorts of things about the lives of the villagers, how could she fail to? But try and draw her out and all you’d get was, ‘I don’t know anything about such things.’

Contraception was rarely used and many women relied on a sponge soaked in vinegar. Some, too desperate to think of the consequences, tried to induce abortions with large doses of gin and nutmeg or herbal concoctions recommended by well-meaning friends, often with near-fatal results. Grandma shut her eyes to it and never gossiped, but I was told by someone else that she had threatened one woman who had dosed herself so often to ‘get rid of it’, that she wouldn’t attend her if she did it again. She wasn’t taking the moral high-ground, but simply thinking of the health of the mother and the welfare of the existing children. Nor do I think she would have carried out her threat.

She moved promptly and efficiently when things went wrong. With no formal training, she had an unerring instinct which told her what to do, when to send for the doctor and that wasn’t done lightly when doctor’s fees took some finding. She mourned with a family when a baby died and many a time she saved both mother and child when both seemed lost. She was skilful, sympathetic and impossible to shock, never showing by the slightest change in her expression, either doubt or revulsion.

That was why we grandchildren were sent away to play on some days when she had to catch up on her sleep, but we were soon chatting together in companionship again, though at the time she never spoke to me of her work; that came later when I was grown up. In those far off days she talked of her own childhood, her early married life and the times in which she lived. She was never too busy to listen to tales of childish doings, to explain mysteries which seemed insoluble to a seven-year-old, to talk of her childhood, the years in which she grew up and married, the hardships she endured, to inculcate in me her own conviction of what was right and proper, her strong sense of duty, her unfailing humour. Her memory lives on in all those who knew her but there are not many of them left now. Perhaps my book will keep it alive a little longer.

Norfolk roots

Mon, 16/09/2013 - 10:21 — Mary

Although I have lived in Cambridgeshire many years, my roots are in Norfolk and I still have family there whom I visit from time to time. I have just come back from one such visit and, as it always does, it threw me back into the past and set me thinking and talking of my childhood. My brother and sister and I used to spend our school holidays with my grandparents in Necton, and during the second world war we were there even longer.

Grandma was an indomitable lady who was midwife, nurse and confidante to the whole village from before the first World War until the coming of the National Health Service in 1948. She was not unique in what she did, there were thousands of women doing the same job. Unqualified, they were referred to as 'the handywoman' or 'the woman you sent for.' And when she was sent for, she always went, whatever the time of day or night.

She lived with my grandfather and a maiden aunt on a small-holding with no electricity, gas, main drains, sewerage or telephone, just four walls and a roof and a few acres of land. The loo was down the garden, the bath hung on a hook on the backplace wall and the cooking was done on the kitchen range When it got dark we sat by the light of an oil lamp and lit our way to bed with a candle.

Grandma was a fund of stories, told when something jogged her memory. When she began with 'That time o'day,' she wasn't talking about hours and minutes but times gone by and I knew there was a story coming, told in her broad Norfolk dialect.

She told me she had run away from home when she was eight. Her mother had died in childbirth and as the eldest of four girls, she was expected to help run the home. 'I didn't reckon a lot to that,' she told me. What she didn’t tell me was that her father brought another woman into the home, which might have had some bearing on it. She walked the four miles from Swaffham to Necton where her grandparents had a brick making business. She was allowed to stay on condition she helped make the bricks. She never went to school again.

I heard about my grandfather's work as a shepherd, their disastrous wedding day, my mother's illness as an infant, helping the doctor take out a child's tonsils on the window sill of a cottage during an earthquake, about the first World War and the Zeppelins. I soaked them all up.

When she died in 1978, the Eastern Daily Press reported it under the headline: THE MOTHER OF NECTON DIES AT 99, a name she acquired because of the number of babies she had delivered in the village.

The church was packed for her funeral and looking back from my seat at the front I wondered how many of the congregation had stories they could tell about her and I decided to ask and write the answers down. My uncle, who was her executor, had some documents, letters, bills and snapshots. I contacted all my cousins and got their stories and pictures too. Fitting identities and dates to these was like a giant jigsaw and I never did get all the pieces to fit. How many of us, I wonder, have boxes of photos and snapshots we've kept but never labelled. I had a pile of them: children without names or ages, people posing in fancy dress, at parties, at work. 'Who is that?' we ask when something prompts us to fetch out the box and rummage through it. Is it Mum or Aunt Audrey? Is that Dad or his brother? And who is on this group picture of an outing. Where were they going? When? Why did Grandad lose his job and why did they move in with his mother in the tiny cottage? And why did Grandad disapprove so strongly of Mum marrying Dad? How did the reconciliation come about? Why did Great Aunt have three sons but never married?

It is such a pity we don't label pictures when we take them or talk more to our parents and grandparents about their lives. My grandmother told me a lot but I wish I had asked more questions. Now everyone of that generation is long gone and their stories are history, but even so new tales sometimes emerge when people have contacted me as a result of reading The Mother of Necton, tales I would like to have included.

Researching for that book motivated me to do something about the box of photographs I had and one Christmas when I had nothing else to do, I fetched it out and began sorting and labelling, though I needed the help of family members to do some of it. The result is two big albums with the pictures in chronological order, all with names and dates. Now whenever I take, or am given, a picture it goes in the album suitably annotated. I like to think my children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren might look at it after I have gone and learn about what, for them, will be times gone by.

The hardback of Mother or Necton is long out of print but an updated version in paperback is available from Amazon or direct from the publisher: larks.press@btinternet.com

The hardback of Mother or Necton is long out of print but an updated version in paperback is available from Amazon or direct from the publisher: larks.press@btinternet.com

My next blog will be about 'the woman you sent for'.