Bletchley Park

Last Thursday, in the interests of research, I visited Bletchley Park. I should think most people have heard of Bletchley Park and the secret work it did cracking the enigma code.

Bletchley Park was simply a country mansion when it was first taken over to be the home of the Government Code and Cypher School in 1939. Here a handful of very gifted and very clever people began the task of cracking the code. A fiendishly difficult task. They were given a head start by the Poles who had cracked an early version before the war and shared what they had learned with Britain and France.

A code, so we are told in the many exhibits, hides the meaning of a message by replacing a word or phrase with another character or set of characters. A cypher replaces each letter in the original message with another letter. Enigma was a cypher system. The machine did not transmit messages. They were first encyphered by a clerk typing each letter into an enigma keyboard according to a series of instructions which came up on a lighted display as the encyphered letter. This had to be written down and transmitted in Morse code by radio and someone at the receiving end would feed the code into another enigma machine set up in exactly the same way as the sender's, which decrypted it. It was these Morse signals that were picked up by listening stations in England. Some were intercepted at Bletchley Park itself, but most were brought from outlying stations by motor cyclists who were out in all weathers. The task of the code breakers was to turn these messages into readable German.

A code, so we are told in the many exhibits, hides the meaning of a message by replacing a word or phrase with another character or set of characters. A cypher replaces each letter in the original message with another letter. Enigma was a cypher system. The machine did not transmit messages. They were first encyphered by a clerk typing each letter into an enigma keyboard according to a series of instructions which came up on a lighted display as the encyphered letter. This had to be written down and transmitted in Morse code by radio and someone at the receiving end would feed the code into another enigma machine set up in exactly the same way as the sender's, which decrypted it. It was these Morse signals that were picked up by listening stations in England. Some were intercepted at Bletchley Park itself, but most were brought from outlying stations by motor cyclists who were out in all weathers. The task of the code breakers was to turn these messages into readable German.

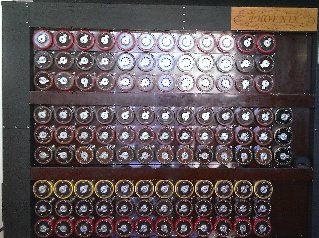

The secret was in the setting up of the enigma machines. Three rotors, marked with the letters of the alphabet, had to be selected from a set of five. The selected rotors had to be located in the machine in the correct order; there were six possible ways to do this. Then the rotors had to be set to their starting positions; there were 26 x 26 x 26 or 17,576 possible way to do this. Then 10 pairs of letters had to be connected on the plug board. The configurations of the machine allowed 158 million, million, million ways. The picture on the right is of the front of the machine.

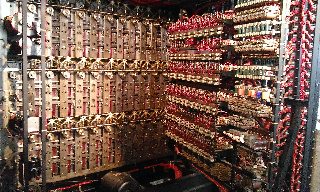

Seems impossible, doesn’t it? It was done by a process of elimination and could not have been done at all without the use of cribs. These were parts of the message which could be guessed at, things like call signs, dates, times, length of message, stock phrases like 'nothing to report' and the German operators being careless and making mistakes. Machines called 'bombes' were developed by Alan Turing and Gordon Welchman to help with the checking and you can see one of these at work at Bletchley. It is amazingly complicated and involves sets of drums, each representing a rotor on the enigma, and at the back a mass of wires and connections. When working, they were hot and very noisy and were operated by WRNS (Women's Royal Naval Service) who were standing their whole shift on concrete floors. Their work was painstaking and fiddly and involved setting the machine up according to a menu obtained from cribs. But the bombes could go through all 17,576 possible positions in 30 minutes.

If the menu worked the machine would stop and those settings were sent to the code breakers, who would apply them to a Type X machine set up like an enigma. If it was viable, plain German text would come up on the display in groups of five letters. That was sent to the translators and afterwards disseminated to whoever needed to know. But few of the recipients knew where the information had come from and were told 'from a reliable source' or made to look like the report of a spy. Sometimes they didn't believe it. But this wasn't a one-off affair, the Germans changed the setting every 24 hours at midnight and the whole process would have to start again. The work went on night and day, 365 days of the year, the aim being to crack the day's code while the information in it was still useful.

If the menu worked the machine would stop and those settings were sent to the code breakers, who would apply them to a Type X machine set up like an enigma. If it was viable, plain German text would come up on the display in groups of five letters. That was sent to the translators and afterwards disseminated to whoever needed to know. But few of the recipients knew where the information had come from and were told 'from a reliable source' or made to look like the report of a spy. Sometimes they didn't believe it. But this wasn't a one-off affair, the Germans changed the setting every 24 hours at midnight and the whole process would have to start again. The work went on night and day, 365 days of the year, the aim being to crack the day's code while the information in it was still useful.

The picture on the left is the back of a bombe machine.

There were also several different types of encrypting machine and the settings for the navy, were different from those of the army, the air force and the secret service. There were also Italian and Japanese machines. And the German High Command had an even more complex one, called Lorenz. Later, a very clever man called Tommy Flowers constructed the Colossus, said to be the forerunner of the modern computer. Most of us can remember the old main frames that took up so much space in offices when they first came about. Now almost everything is computerised and those of us who are not technically savvy have had to learn to use the technology.

I had already read several books on the subject of Bletchley Park and the enigma, but going round the ground floor of the mansion and round the huts that have been restored certainly gave me an insight into the work that went on there and the security that protected it.

Towards the end of the war, around ten thousand people were working at BP and its scattered outposts. Some were in the services, some were civilians, but rank and uniform counted for very little. Each had his or her allotted task and, apart from the people they worked with, had no idea what others were doing. Mail was sent all over the country by motor cycle to be posted so that Bletchley was never identified. With so many people of both sexes working in such a close atmosphere, romance was inevitable and produced several weddings. There is one story that a couple who married after the war did not know that each had been working at Bletchley Park until the secret came out in the seventies. Ten thousand people keeping such a vast secret is difficult to comprehend nowadays, but keep it they did. And the work that went on there is said to have shortened the war by at least two years.